- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

Ezy Reading: When Silencing The Critics Hurts The War Effort |

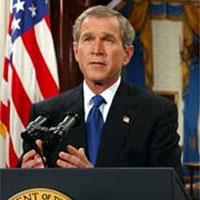

Perhaps one of the most worrying aspects of Bush administration rhetoric over the past year left largely unabated has been their ongoing charge that criticism of the war in Iraq endangers U.S troops on the ground, and ‘emboldens’ our enemies. While it is fair to concede that opposition to a war through such varying forms as peace marches and public speeches could serve as encouraging to an opponent, that is never in itself a reason worthy enough to silence critics.

In the first instance, it is important to recognize what much of the White House’s appeal for calm represents. That is, a fairly defensive salve that tries to connect critique of the conflict and those in the administration who are driving the war, with the men and women who are merely fulfilling their duties of military service. With rare exception has the anti-war sentiment expressed over the past few years been directed at U.S troops. Naturally, there have been instances where specific individuals were targeted, as in the case of the Abu Ghraib prison scandal, however even there, most were agreed that this was not a fair representation of the quality, moral practice, and overall character of America’s armed services. Rather, and let us be clear on this: the majority of those in opposition to the conflict today have a problem with our leadership and their plan for resolution, rather than with any of the troops serving -at considerable risk and potential sacrifice- on the front lines of Iraq.

Just last month, on Veterans Day, President George Bush contended that the Democratic Party’s repeated allegations about mishandling of pre-war intelligence was “deeply irresponsible” and would “send the wrong signal to our troops and to an enemy that is questioning America’s will.” Vice-President Cheney has taken a similar, if more aggressive tact, forcefully attacking those Democratic lawmakers now in opposition to Iraq who voted to authorize the war in 2002. Unfortunately, these lawmakers could only vote to go to war on the evidence they were presented with, and what the ongoing C.I.A leak investigation suggests is that the Bush administration knew the platter of evidence they were serving up to the public was loaded with false constructions and twisted suggestion. So really, what George Bush was perhaps conceding he most feared while passionately defending American troops on Veterans Day was that he’d hate for the people he sent to risk their lives in Iraq to discover they needn’t have been there in the first place.

Gone in the President’s rebuttals are the earlier legitimating arguments for war and preventing potential nuclear, biological and chemical weapons manufactured in Iraq from being used against Americans and other innocents. Instead, he has replaced this with louder, voluminous talk that frames the conflict as forming part of the ‘ongoing global war on terror’. This, even as it now seems abundantly clear that the majority of terrorist insurgents in Iraq were a by-product of American occupation, and absent under even Sadaam Hussein’s brutal regime. Afghanistan, on the other hand, was a different case altogether, where proof of Al Qaeda’s position in that country post 9-11 has always been certain.

Gone in the President’s rebuttals are the earlier legitimating arguments for war and preventing potential nuclear, biological and chemical weapons manufactured in Iraq from being used against Americans and other innocents. Instead, he has replaced this with louder, voluminous talk that frames the conflict as forming part of the ‘ongoing global war on terror’. This, even as it now seems abundantly clear that the majority of terrorist insurgents in Iraq were a by-product of American occupation, and absent under even Sadaam Hussein’s brutal regime. Afghanistan, on the other hand, was a different case altogether, where proof of Al Qaeda’s position in that country post 9-11 has always been certain.

Similarly erroneous has been the line of argument from conservative quarters that Democrats would do well to back off the administration lest they risk being ‘on the wrong side of history.’ It is true that there has definitely been something of a ‘new wave’ of democracy spreading throughout the Middle East during the course of 2005, touching, in varying degrees, Iraq, Afghanistan, Palestine, Egypt, and even Saudi Arabia. And few would disagree that the world is safer when someone like Hussein is not in power. That said, what is only the possible, and far from proven democratisation of a region should never be held as a counter against vocal opposition to an administration and their course of action. Nor does progress suddenly validate what may have been bullish, deceptive behaviour that was used to reach that point in the first place.

In an appearance on NBC’s Meet the Press earlier this year Kate O’Beirne of the National Review offered that “... given the remarkable things that appear to be happening in that part of the world (the Middle East), I think the Democrats have to be extremely careful not to sound so resentful and pessimistic.” She went on, “Any party that appears to be welcoming a defeat for America because that's good for them politically is in a terrible position.” True enough, until they gathered some welcome momentum in the last two months, it has appeared for far too long that the Democratic Party had become a feckless opposition, playing tit-for-tat politics rather than offering substantial alternative solutions to prevailing issues of contention. But just as it is flawed to make the assertion that criticism of the war in Iraq hurts troops on the ground, so too is a warning that opposition should effectively keep their mouths shut because they might not come off looking so good in the future. Surely this isn’t the kind of passive, self-preserving leadership we expect from our lawmakers?

In an appearance on NBC’s Meet the Press earlier this year Kate O’Beirne of the National Review offered that “... given the remarkable things that appear to be happening in that part of the world (the Middle East), I think the Democrats have to be extremely careful not to sound so resentful and pessimistic.” She went on, “Any party that appears to be welcoming a defeat for America because that's good for them politically is in a terrible position.” True enough, until they gathered some welcome momentum in the last two months, it has appeared for far too long that the Democratic Party had become a feckless opposition, playing tit-for-tat politics rather than offering substantial alternative solutions to prevailing issues of contention. But just as it is flawed to make the assertion that criticism of the war in Iraq hurts troops on the ground, so too is a warning that opposition should effectively keep their mouths shut because they might not come off looking so good in the future. Surely this isn’t the kind of passive, self-preserving leadership we expect from our lawmakers?

Most importantly however, these barbs from conservative quarters challenge fundamental democratic principles of reasoned party and policy opposition, which thus expose them raw as little more than desperate survival tactics. Without the ability to promote alternative courses of action, and to challenge those in power we put at risk the very core ideals of this nation’s founding fathers. When we question those in command we get our humvees re-fitted with better armour. We get the bad apples out of Abu Ghraib. We get diplomacy as a solution over bloodshed. And we hopefully pressure our leaders into offering, at last, a real, definitive plan of action instead of letting them merely pay for good headlines and deflect questions by telling us that those very questions are hurting our troops.

Most importantly however, these barbs from conservative quarters challenge fundamental democratic principles of reasoned party and policy opposition, which thus expose them raw as little more than desperate survival tactics. Without the ability to promote alternative courses of action, and to challenge those in power we put at risk the very core ideals of this nation’s founding fathers. When we question those in command we get our humvees re-fitted with better armour. We get the bad apples out of Abu Ghraib. We get diplomacy as a solution over bloodshed. And we hopefully pressure our leaders into offering, at last, a real, definitive plan of action instead of letting them merely pay for good headlines and deflect questions by telling us that those very questions are hurting our troops.

It’s those troops we’re looking to help perhaps most of all.

Ezy Reading is out every Monday.