- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

June 2011 - Towards The Resources End Game |

Governments of the world are showing renewed interest in the resources industry. Recently, what would appear to be boring or routine energy deals have involved heavy diplomatic maneuvering, extensive government effort, and featured country presidents at signing ceremonies. At the same time, large oil consuming countries continue to reliably intervene in regional conflicts that involve oil-rich countries.

Governments of course have always shadowed the resources industry, and competition and conflict over resources are nothing new. For centuries, villages, tribes and countries have conflicted over disputed waterways, timber and mineral resources.i The protection of oil resources and transport lines was paramount in both World Wars of the 20th Century. Protection of Saudi Arabia’s oil reserves was a serious consideration in the US foreign policy stance of the 20th Century, and also in its decisions to go to war with Iraq in 1990 and 2003.

However, against the backdrop of unprecedented growth in global demand for oil and potential future scarcity, government involvement is becoming more explicit and widespread, and governments of major powers have flagged that military intervention will be an option to secure supply of this strategic resource. Oil in particular is a highly strategic resource because it is now enmeshed in the very fabric of our existence. Few consumer products do not contain or rely on a petroleum product during production and distribution. Consumer services, transport, construction, manufacturing and the military all rely heavily on oil to function. The world’s oil requirement is set to grow, pending no technological breakthrough to yield an alternative.

Views as to where it will all end range from the possibility of widespread conflict triggered by resources quarrels, to more optimistic, climate-friendly solutions fueled by renewable energy and new technologies.

This essay plots the progression towards the resources endgame: a time when energy demand will outstrip supply and the interests of large energy consumers and will be pitted against each other and against suppliers. It looks at the predicted rates of growth and demand for oil, the question of supply, and outlines the roles of the key energy protagonists including the approaches to energy security by the US and China, followed by the reciprocal maneuverings of key petroleum suppliers: OPEC countries and Russia. Finally, the overall trend of resources nationalisation, and the potential role of technology to mitigate the risks, is discussed.

The rising tide

Global resources demand is growing rapidly, in line with population increases and industrialisation in the developing world. Demand has been growing faster than production, as evidenced by a sustained period of rising commodity prices from 2003. In 2011, gold and copper prices reached new record highs, while other commodities have skirted stratospheric levels.

The pinch of demand and supply, and the effects of geopolitics and conflict, are no more evident than in oil. The price of oil has been highly volatile and rising since 2003, mainly reflecting an elevated risk premium for Middle Eastern oil supply (conflict in Iraq, Gaza, Libya and Yemen), and rampant global demand growth and sluggish supply response. For example, oil prices soared from USD20-30/bbl in 2003 to USD147/bbl in 2008 and crashed to USD40/bbl at the start of 2009, returning to USD110/bbl in early 2011. The rapid rise of China and India, coupled with the coordinated global economic growth of the period 2003-2008, have seriously ramped up the world’s energy requirements. According to the US Government DOE, global oil demand grew at approximately 1.5% per annum over this period, while global supply was almost stagnant. New discoveries of oil have failed to keep pace with demand growth. Many believe that the cheapest and easiest oil discoveries have already been made, and that future deposits will be harder to find and more expensive to extract. These developments have helped usher in the new era of high energy prices, inspiring analysts such as Paul Roberts – author of The End of Oil, to suggest that the era of cheap oil is over.

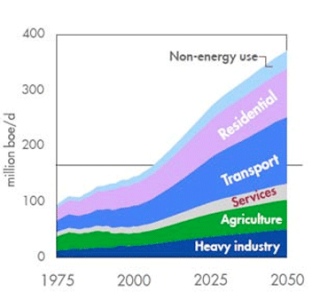

With global growth showing no signs of slowing, this price instability is set to continue. According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) latest World Energy Outlook, global energy demand will rise by 36% by 2035, with China and India accounting for the majority of growth. Not surprisingly, the economic growth and improved living standards in China and India will lead to a corresponding growth in demand for mobility and electrification that will be fueled by oil and coal. Chinese energy demand will increase by 75% over this period, with most of the incremental demand being for fossil fuels: coal, oil and gas. Energy consumption will be paramount to the improved living standards of the Chinese population. Accordingly, the IEA predicts that global oil demand will nearly double by 2030.

Not surprisingly, the economic growth and improved living standards in China and India will lead to a corresponding growth in demand for mobility and electrification that will be fueled by oil and coal. Chinese energy demand will increase by 75% over this period, with most of the incremental demand being for fossil fuels: coal, oil and gas. Energy consumption will be paramount to the improved living standards of the Chinese population. Accordingly, the IEA predicts that global oil demand will nearly double by 2030.

The IEA expects production of conventional crude oil to plateau at current levels, with the incremental production to be sourced from unconventional oil (tar sands, shale oil and deepwater deposits) and natural gas liquids. For example, according to the US DOE, already 20% of US oil imports are supplied from Canadian tar sands. Unconventional deposits are more expensive, more difficult to extract and environmentally riskier – note the Deepwater Horizon rig disaster in 2010.

Two compelling messages emerge from the IEA: 1) conventional oil production has peaked or will peak very soon, and by 2035, almost all conventional oil production that does occur will be met by production from fields that are yet to be discovered. It could be optimistic to assume that the shortfall of production from existing conventional fields will be conveniently met from new fields. However, recent large finds in Israel and Venezuela lend some hope.

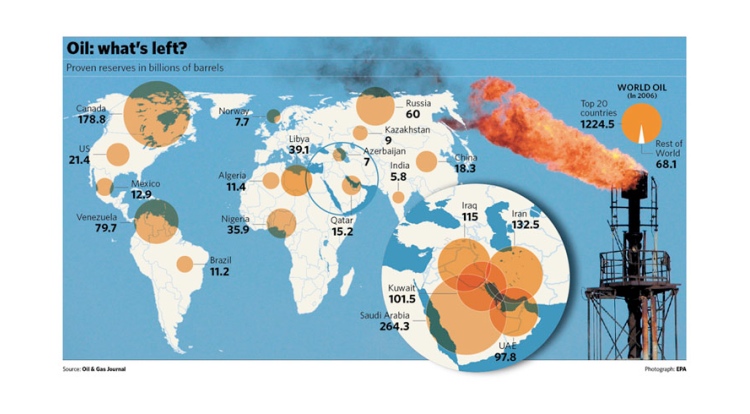

It is clear new conventional oil production will largely be sourced from OPEC countries, which currently hold 75% of the world’s known oil reserves. OPEC countries including Saudi Arabia supply about 30% of world oil consumption – therefore non-OPEC sources still account for most of the world’s oil supply and largely keep the balance in terms of supply security. However, non-OPEC production will eventually fade as these countries simply do not have the conventional reserves base of Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Iraq and Iran - the result being, the second compelling message from the IEA - 2) the focal point for global supply of the strategic, precious resource - oil, will be the most politically unstable regions on the planet.

When oil becomes scarce, the Middle East and North Africa region will be elevated to a status in global matters beyond its historic place, and well beyond its proportionate direct economic and military weight. While the oil shocks of the 1970’s were temporary, this will be the oil end game. The alternative to Middle Eastern oil will be riskier and expensive unconventional oil, such as deepwater oil and the mammoth tar sands oil deposits beneath the currently protected Alaskan wilderness.

Peak oil: when do we run out?

The inability of oil supply to ramp up to meet demand during 2003-2008, and the high prices that followed, have set alarm bells ringing for governments across the globe. Everyone’s economy is heavily reliant on oil, and when prices rise it hurts the economy. The perceptions of oil scarcity therefore flow into tensions around supply and demand, lead to erratic and speculative trading behavior, and ensure anxiety over securing long-term contracts on behalf of buyers. Even at current (June 2011) prices of USD100/bbl, many market analysts are still calling bullish on oil for the coming years.

According to BP, there are 1.3 trillion barrels of proved reserves of oil left in the ground.ii This figure is inflated to 1.5 trillion barrels, if Canadian tar sands are included. BP estimates a reserve to production ratio, based on current production levels, for conventional oil of 45.7 years. While that does not sound too bad, the notion of scarcity relates not only the risk of running out, but also to the rate and the cost at which the remaining oil can be recovered. As oil fields run out, the remaining oil in the existing fields is more costly and difficult to extract, requiring water or gas to be pumped into the reservoir to maintain the pressure that allows extraction.

On these grounds, oil will likely become expensive long before it runs out. This is the thesis of Paul Roberts in The End of Oil, that the economic pain of oil scarcity will be felt long before it runs out – precisely the current predicament of high oil prices.

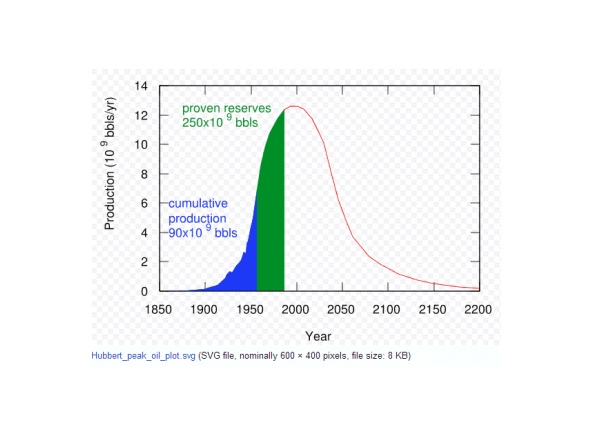

In terms of the rate at which oil can be produced to meet future demand, there is an established body of thought that predicts oil production cannot grow forever. There will be a global peak oil production moment, beyond which oil production will begin to fall. We will not immediately run out of oil, but beyond that point the rate at which existing oil fields are depleted will outstrip the rate at which new fields are brought into production. This is peak oil theory.

Peak oil theory flows from the famous work by petroleum geologist M. King Hubbert in the 1950’s. Hubbert observed that the typical production profile of an oil field was similar to a logistic curve, or what is sometimes referred to as a bell curve. Initially, oil production ramps up rapidly under the natural pressures that exist in an oil reservoir deep in the earth. As the production continues over time and the oil field depletes, the pressure in the reservoir drops off and the rate at which oil is extracted also drops off. Petroleum engineers employ various techniques such as pumping water, carbon dioxide or natural gas back into the reservoir to increase reservoir pressure and enable continued extraction.

However, it is a losing battle and as all good things come to an end, so do oilfields. Hubbert postulated that the production behaviour of many oil fields, even when aggregated across an entire country, would also conform to a logistic curve. The logistic model developed by Hubbert was used to accurately predict the peak in US oil production between 1965 and 1970. This extrapolation has been taken a step further to model the production behaviour and eventual decline of oil fields globally. The obvious implication is that once ‘Peak Oil’ has passed, production rates will commence a steady decline causing untold impacts for the global economy. Estimates of the timing for Peak Oil, based on calculations on existing oil fields and potential new discoveries, vary from the pessimistic to the optimistic – some believe it will occur next year (every year) and others believe it will occur sometime after 2020. Others believe that any supply deficit will be plugged by new fields and unconventional oil resources, and that any peak in oil production is hundreds of years away.

Global leaders know oil is critical. They know that the globe is consuming and will consume ever-growing amounts of it, and that production is struggling to keep pace with demand. Furthermore, according to peak oil theory, global production one day may start to fall.

Against this background, the world’s oil protagonists on the demand and supply side have been playing their role in a high stakes global energy game.

From the decks of the USS Quincy in 1945 to Iraq

One of the most powerful and enduring international relationships of the last century is that of Saudi Arabia and the US.

In February 1945 on the foredecks of the heavy cruiser USS Quincy - patrolling the waters of the Persian Gulf, a pivotal agreement was reached between the ailing US President Franklin Roosevelt and the Saudi Monarch King Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud. They agreed to a tacit alliance whereby the US would provide Saudi Arabia – and the Saudi Royal Family itself – an umbrella of security in return for privileged access to the mammoth oil reserves beneath the sands of the Saudi Arabian deserts. The Arabian-American Oil Company (Aramco) was then established to provide the western expertise necessary to discover and extract Saudi oil reserves and deliver them to US-bound super tankers. In the fifty years since, billions of barrels of oil were transferred under this gentleman’s agreement.

To fulfill the security side of the Roosevelt-Ibn Saud alliance, a US Air Force base was established at Dhahran, a US Army base was established at Khobar Towers and the US Navy set up a base in neighbouring Bahrain, plus associated intelligence and military technology sharing. All such installations were intentionally located to triangulate Saudi Arabia’s and the world’s largest ever oilfield – the colossal Ghawar. The alliance was evidenced by the US defence of Kuwait in the 1991 Gulf War, not only to halt Iraq’s invasion of that country but also to halt progress towards Saudi Arabia’s borders. The US made great use of its Saudi Arabian bases for missile launches, a base for fighter jet sorties into Iraq and support to troops on the ground. This, and the response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980’s showed that the US were willing to step in when Saudi Arabia’s borders were even remotely threatened.

President Carter summed up his Government’s approach to defending US oil interests in his State of the Union Speech in 1980 (now known as the “Carter Doctrine”):

...The region which is now threatened by Soviet troops in Afghanistan is of great strategic importance: It contains more than two-thirds of the world's exportable oil. The Soviet effort to dominate Afghanistan has brought Soviet military forces to within 300 miles of the Indian Ocean and close to the Straits of Hormuz, a waterway through which most of the world's oil must flow. The Soviet Union is now attempting to consolidate a strategic position; therefore, that poses a grave threat to the free movement of Middle East oil.

...Let our position be absolutely clear: An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.

The explicit Saudi-US alliance endured almost unbroken until the late 1990’s, when it became a casualty of broader ideological and religious cracks spreading between the Middle East and the US, and the generally deteriorating political and security situation in the Middle East region. It is well known that Osama bin Laden and other local characters were enraged at the US Military presence in Saudi Arabia, and a stated ambition of his al Qaeda was to forcefully remove all Americans from North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. The group was responsible for the attack on the USS Cole in Yemen in 2000 and the US Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998. The 1996 bombing of Khobar towers, a large residential complex housing US military personnel near the Dhahran headquarters of Saudi Aramco, that killed 19 US servicemen and injured over 300 others of many nationalities, was tracked to Hezbollah.

While the US military presence in Saudi Arabia has diminished in recent years, the approach has not changed. Whenever the free supply of oil has been threatened, such as regional conflicts in oil-rich nations such as Libya and Yemen, or threats to critical supply routes such as piracy in the Suez Canal, the US has intervened. At the same time, countless civil wars and bloodshed have been ignored in strategically less important countries across the globe.

Enter the Dragon

A recent oil and gas deal between China and Russia shows that the security of national energy supply ranks highly in the foreign policies of these two major economies. Fierce adversaries in the past, the countries now share a relationship of convenience motivated by mutual needs and smoothed by an essential lubricant: light, sweet crude oil.

Under the deal announced in 2009, China will purchase up to 300,000 bbl/day of crude oil from Russia for the next 20 years, via a new oil pipeline stretching from Siberia to Daqing in the Northeastern province of Heilongjiang.

The oil and gas deal was not launched by energy company CEOs, town mayors or dignitaries but by the Russian and Chinese Presidents. This heavy-duty involvement in what would otherwise be considered a rather dull transaction reinforces the importance of energy resources in the minds of policymakers. A Russian delegation that included President Dimitry Medvedev, visited Chinese President Hu Jintao in Beijing in September 2010 to mark the completion of the 999km pipeline. China secured the 20 year oil supply deal via an oil-for-loans arrangement under which China will provide USD25 billion in loans today, in exchange for the secure 20 year sales contract on favourable terms. Both China and Japan contested a fierce diplomatic and commercial battle to secure the destination of this all-important pipeline and its precious contents. The media reported that Chinese officials were irked by Japanese attempts to usurp Sino-supremacy over the pipeline and its cargo. However, it was the Chinese who eventually prevailed with their winning combination of dollars and petro-diplomacy.

The China-Russia deal provides a neat fit for both countries. On the one hand Russia was seeking to diversify its sales exposures away from debt-laden Europe and at the same time tap into the fast growing Chinese economy. On the other, China was looking to diversify its sources of energy away from the politically unstable Middle East.

Such security of supply is a prime consideration for China now more then ever – in 2010 it surpassed the US as the world’s largest energy consumer.

The Russia-China energy deal also marks a landmark development in Sino-Russia relations. The two countries have experienced a turbulent relationship throughout history, including border conflicts, annexations and trade disputes. Relations eventually thawed somewhat, culminating in military treaties and other strategic alliances. Energy and resources cooperation have been critical to the improved relations between these two economic giants.

China’s energy companies, the largest of them CNOOC, CNPC and Sinopec, are state-owned - anything that involved energy typically involves the Government. China’s energy strategy includes government-to-government deals and cooperation (win-win deals), acquisitions of strategic offshore assets, and protection of opportunities in terms of new reserves and strategic supply routes – the latter involving military backup as needed. As with the US, historically China has been willing to get its hands dirty with some of the world’s most unsavoury governments, such as Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Nigeria and Iran. China’s military activities in the disputed regions of South China Sea have almost always accompanied oil and gas exploration and development activities. There have been numerous disputes between China and smaller countries in the region over potentially oil-rich islands – particularly with seemingly overlapping claims to the same territory. China’s recent decision to place a deepwater drilling platform in these waters was accordingly labeled by some analysts a as China’s “oil drill weapon”.

In 2005 the assets of the Californian oil company UNOCAL were up for sale. The US energy powerhouse Chevron was frontrunner for the deal and the popular favourite. Late in the piece an unlikely bidder for the assets emerged in the form of Chinese Government-owned China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC). This bid was put down by US Congress on National Security Grounds. This treatment of an energy deal underscores the seriousness with which both Chinese and US Governments view energy resources.

Supply side - the oil weapon: using and abusing it Part 1

As described above, the world’s oil reserves are concentrated in politically unstable regions – notable among them the Middle East. Not only are there recurrent threats to the security of supply from conflict within and between countries from these regions, the countries themselves cannot always be relied on by consumers for security of supply.

The world experienced what is called an “oil shock” in 1973 (and again in 1979). In 1973 this occurred when OPEC countries placed an embargo on oil supply in protest of US support for Israel in the Yom Kippur war with Syria and Egypt. OPEC raised oil prices by 70%, and reduced total production in 5% increments, as well as a total embargo on sales to the US, until their political objectives were met. At the time, an OPEC spokesman proclaimed the use of the “oil weapon” against the west. The oil shock had serious economic impacts on the US and prompted a period of fuel rationing and an extended period of high fuel prices and inflation. It also provided a catalyst for the eventual penetration into the western world of smaller, fuel-efficient motor vehicles that were mass-produced by Japanese companies such as Toyota.

Russia’s emerging status as an energy heavy hitter: using and abusing it Part 2

The China-Russia deal exemplified Russia’s status as a serious regional energy player. Since going into recession after the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russia has recently enjoyed a clout in regional and global affairs disproportionate to its own economic weight. However, perhaps the Chinese should choose their bedfellows wisely.

Russia, endowed with the world’s largest gas reserves and well up the merit order on oil, has used this resources weight to clobber its regional adversaries, pressure counterparty nations on trade deals and as a bargaining chip in international negotiations. Not surprisingly, the current President of Russia, Dimitry Medvedev is an oil and gas man and former CEO of Gazprom – Russia’s Government-owned natural gas behemoth. During the recent commodity price upswing described above, Russia has become tremendously wealthy, steadily clawing its way back up the global GDP rankings. Russia is the world’s largest natural gas producer and exporter, supplies almost a quarter of Western Europe’s gas consumption, and is the world’s second largest oil producer. Western European countries are connected to Russia’s oil and gas by the world’s biggest network of pipelines, almost entirely owned by Gazprom.

These steel tentacles extend Russia’s power deep into the hearts of the countries that it supplies.

The latter -including Greece, Austria, Ukraine, Poland, Germany and France- despite attempts at diversification have little choice but to rely on Russian energy to warm their populations during the cold and bitter winters.

The state control of Russia’s vast energy resources is no coincidence. When Vladimir Putin took power of Russia, he quickly unwound the resources privatisation process championed by his predecessor Boris Yeltsin. Private energy companies were commandeered by the State, with full knowledge that their resources and infrastructure could be leveraged to restore Moscow’s commanding role in global affairs.

In January 2009 Russia flexed its resources muscle by shutting down gas supplies to most of Europe following a dispute with Ukraine over gas prices and unpaid fines. The supply halt was particularly devastating given it occurred amidst plummeting temperatures and snowfalls of an unseasonably cold European winter. Russia stopped gas supplies through Ukraine to Bulgaria, Hungary, Greece, Turkey, Romania, Serbia, Bosnia and Macedonia. According to media reports at the time, the government of Slovakia declared a national emergency; children were being sent home from school in Bulgaria, Austria, and Italy reported falls in gas supply of 90 per cent; France said Russian supplies had tailed off 70 per cent, and Germany also reported declines. The actions drew a chorus of criticism from all over Europe as countries felt they had been held hostage to Russia’s resources dispute.

Russia released a national security strategy document in January 2009 that identified Russia’s main concerns as 1) a widening arms gap with the US and 2) increasing competition for the world’s oil and gas reserves.

Taxing times: the curse of resource nationalisation?

Other governments across the globe are preparing themselves for the uncertain resources future and the waves of high prices and revenue opportunities that are expected over the longer term.

In Australia, the Government recently proposed an aggressive new tax, known as the “Resources Super Profits Tax”, to apply to all minerals projects at the rate of 40% above a certain threshold (the risk free rate). The rationale for the new tax was threefold – to try to simplify a complex state royalty system, to centralise resources revenue and to simply increase the tax take from resources companies when they are highly profitable. The latter makes sense for the Government given it is expected that Australia will experience uplift in demand for commodities accompanied by high prices for the next 10-20 years.

The latter makes sense for the Government given it is expected that Australia will experience uplift in demand for commodities accompanied by high prices for the next 10-20 years.

Recently Rio Tinto CEO Tom Albanese decried “the curse of resources nationalisation” as governments across the globe are raising taxes, increasing their stakes in projects or companies, blocking deals or expropriating assets. For example, in 2010 in Kazakhstan a law was enacted to enforce that private property, such as resource assets, can be seized by the Government “as last resort” and “when national security is threatened”. The Norwegian Government takes 90% of revenues from its oil and gas sector through royalties or ownership and owns 71% of the Norwegian oil and gas company (Statoil). In Saudi Arabia, the Government 100% owns Saudi Aramco – the world’s largest single oil supplier. Bolivia achieves royalties and taxes of 50-80%. Mexico and Russia have nationalised oil companies. According to the Energy Studies Review: "between 1973 and 1982, companies lost around 50% of their share of the crude oil market, from 30 million barrels per day (MMbbl/d) to around 15.2 MMbbl/d”.

The role of technology

The future also lies with the engineers and scientists. As the price of oil rises, the options for alternative fuels and technologies that are currently too expensive have the potential to open up.

Hydrogen fuel cells are often touted as a possible replacement for conventional petrol combustion engines, but the mainstream rollout of this technology is faced by a number of challenges. Firstly it involves a wholesale rebuilding of the world’s petrol supply infrastructure. There are also safety concerns (around flammability) that are yet to be overcome, and environmental issues associated with the use of electricity to derive hydrogen. However, hydrogen is highly abundant – the world will never run out of it, it is present in air, sea and freshwater and in George W Bush’s 2001 State of the Union address, a template was put down for the transition of the US to a hydrogen economy over the next few decades.

Alternative fuels, such as ethanol and biodiesel, are technologically and economically feasible, although their widespread use has deleterious effects for food prices.

Similarly, most car manufacturers are trialing or currently sell electric/electric hybrid cars which could feasibly penetrate the car market once infrastructure issues and environmental concerns over the source of the electricity (eg coal-fired electricity in light of CO2 emissions concerns) are resolved. It is only glossed over at the end of this essay, but the ability of the world to wean itself off oil dependence and onto more secure, reliable energy sources would be a significant breakthrough that clearly would alleviate the issues described above.

Where will it end?

Energy geopolitics is no longer the exclusive preserve of the US but now also includes China and Russia. One by one across the globe, governments are jumping into the ring as counterparties or shadow participants on both the demand and supply side of energy deals.

Against the background of scarcity or even perceived scarcity of resources, and ever-growing demand for these resources, it is understandable why: more and more energy is required to support growing and industrialising populations, underpinning economic growth and welfare, to the extent that these requirements can be viewed as national security issues, with the serious implications that follow. On the supply side, as prices rise the resources revenue take becomes all the more crucial to economic growth, which also draws governments in to claim their share of revenue.

On the supply side, as prices rise the resources revenue take becomes all the more crucial to economic growth, which also draws governments in to claim their share of revenue.

The world’s major superpowers, such as the US and China, have prioritized security of energy supply and have postured aggressively towards achieving it. While those that hold the energy resources, Russia and OPEC, have shown a willingness to use their resource power as a geopolitical lever against their adversaries when needed. The coming shortages of energy over the next fifty years, and perhaps sooner, will amplify the seriousness of these conflicting objectives, which will lead to growing tension, rising prices, alliances of necessity, strengthening rhetoric and perhaps worse. Where resource and reserve delineations are poorly defined or shared between borders, or are not freely available to consuming regions, energy deals may not merely be facilitated, but enforced.

When we are in the energy endgame of soaring demand and dwindling oil supplies as envisaged by the IEA, and energy is the pre-eminent national security consideration, will Carter’s doctrine be borne out? The rhetoric of the governments of major powers on energy now draws a solid link between energy and those national security lines. Governments have always been willing to enter into conflict when it was necessary or justifiable on national security lines. Does this open the door to large-scale conflict over resources? Circuit breakers include the discoveries of vast new reserves, such as those recently announced by Israel, or new technologies and renewable energy.

ENDNOTES:

i. History is littered with military struggles and interventions motivated by resources – but they have typically been regional skirmishes and not widespread: pre-revolutionary Iran and the US/UK; pre-Chavez Venezuela and the US; Nigeria-UK; Burma and France (and now Burma and China); Russia and Central Asia and the Caucasus; Mobutu’s Zaire and France; South Africa prior to the 1990s with the UK and the US - the so called Rhodes-era ‘scramble for Africa’.

ii. Proven reserves are estimated quantities that analysis of geologic and engineering data demonstrates with reasonable certainty are recoverable under existing economic and operating conditions.

Cameron O'Neill works in banking in Sydney, Australia and supports the National Depression Initiative. To help out or learn more please visit: www.beyondblue.org.au