- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

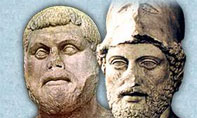

Themistokles and Perikles of Athens |

In part two of his focus on leading figures in Ancient Greece, this month John Paladaris looks back at Themistokles and Perikles, comparing the contrast between their individual characters and methods, and assessing their overall roles in the ongoing development of the Athenian state.

Themistokles and Perikles of Athens played critical roles in influencing the development of the history of Athens and, on a broader level, the entire history of Greece. Plutarch informs us that Themistokles' family was "too obscure to have lent him any distinction at the beginning of his career" (though he was still descended from a wealthy branch of the Lycomid clan) whilst Perikles was descended from the tribe of Acamantis and the deme of Cholargus, and on both sides from the noblest lineage in Athens (his father was Xanthippus and his mother was Agariste, a niece of Kleisthenes). Though their backgrounds were in contrast, both men were particularly important products of the fifth century. Themistokles was principal in laying the foundations for the pre-eminence of the Athenian state during the period, and in contributing to the defeat of the Persian invaders under Xerxes. Perikles, by contrast, was influential in the creation of radical democracy during his extended leadership of Athens, but he also was significant in the outbreak of the most dramatic conflict of the Hellenic world, the Peloponnesian War.

Themistokles was elected to the archonship in 493-2, and served as strategos at Marathon in 490. He was an ambitious and at times unscrupulous leader, and wanted more reforms to the Kleisthenic constitution. In the same turn, however, Themistokles showed during his career that he was in favor of progress; he displayed considerable foresight, and strong convictions. He is ascribed with having implemented two major 'democratic' constitutional reforms in 487: the introduction of ostracism, and the replacement of election by the casting of lots as the method of appointing archons. Both reforms would have helped to relieve clan rivalries in Athens and to remove opponents to Themistokles- in fact in 483-2 Aristides, Themistokles' chief rival, was ostracized.

Themistokles was elected to the archonship in 493-2, and served as strategos at Marathon in 490. He was an ambitious and at times unscrupulous leader, and wanted more reforms to the Kleisthenic constitution. In the same turn, however, Themistokles showed during his career that he was in favor of progress; he displayed considerable foresight, and strong convictions. He is ascribed with having implemented two major 'democratic' constitutional reforms in 487: the introduction of ostracism, and the replacement of election by the casting of lots as the method of appointing archons. Both reforms would have helped to relieve clan rivalries in Athens and to remove opponents to Themistokles- in fact in 483-2 Aristides, Themistokles' chief rival, was ostracized.

Themistokles' major achievement, however, was the creation of Athenian naval power, which grew out of his insightfulness in recognizing the potentialities for Athens if she sacrificed her army to the navy to make Athens a sea-state. Upon his election to the archonship Themistokles had carried through the Assembly a proposal for the fortification of the peninsula of Piraeus. This measure was primarily allowed due to the hostility of Aegina at this time, and Herodotus tells us that it was also based upon such hostilities that in 483 Themistokles convinced the Athenians to direct the money produced from the silver mines at Laurium towards the construction of two hundred warships, instead of sharing the money out amongst themselves. By about 480 Athens had nearly two hundred triremes under her command, and it was these very warships which laid the foundation for the Athenian naval power that was to prove so critical not only in the Persian Wars, but as a major factor in the Peloponnesian conflict. As Herodotus states:

'The outbreak of war at that moment saved Greece by forcing Athens to become a maritime power. In point of fact the two hundred ships were not employed for the purpose for which they were built, but were available for Greece in her hour of need.'

Upon the second Persian invasion of 480-479 under Xerxes, Themistokles wisely proposed the recall of exiles (including Aristides), arranged for a Spartan alliance and took other measures to facilitate resistance. Plutarch states that "Themistokles is generally regarded as the man most directly responsible for saving Greece..." by his decision to surrender command of the Greek forces to Eurybiades and the Spartans' so as to avoid division and maintain a unified opposition to Persia. He himself led Athenian forces in the valley of Tempe in Thessaly and at Artemisium, but it was mainly upon Themistokles' brilliant combination of sound strategy and trickery that the crucial naval battle at Salamis was fought in a restricted area, thus preventing the Persians from deploying their fleet properly and leading to the decisive Greek victory.

Upon the second Persian invasion of 480-479 under Xerxes, Themistokles wisely proposed the recall of exiles (including Aristides), arranged for a Spartan alliance and took other measures to facilitate resistance. Plutarch states that "Themistokles is generally regarded as the man most directly responsible for saving Greece..." by his decision to surrender command of the Greek forces to Eurybiades and the Spartans' so as to avoid division and maintain a unified opposition to Persia. He himself led Athenian forces in the valley of Tempe in Thessaly and at Artemisium, but it was mainly upon Themistokles' brilliant combination of sound strategy and trickery that the crucial naval battle at Salamis was fought in a restricted area, thus preventing the Persians from deploying their fleet properly and leading to the decisive Greek victory.

After the Persian invasion and until his own ostracism in 472 on accusations of corruption and attempting to negotiate a peace agreement with Persia, Themistokles encouraged a policy of rebuilding Athens, and for the fortification of the city and Piraeus via the construction of the 'long walls' since, as Plutarch offers, "... he had already taken note of the natural advantages of Piraeus' harbor and it was his ambition to unite the whole city to the sea." Though it is difficult to tell if Themistokles himself implemented the measures, during this period the trierarchy system was also introduced for the state furnishing of triremes; positions in the navy were opened up to even the poorest classes in Athens; and the position of strategos was constitutionally amended to become a publicly elected position with broader commanding powers for generals.

Themistokles was important in the development of the history of Greece, therefore, because his reforms continued the radicalism of Athenian democracy at the expense of the aristocratic classes, and he ensured that his plans for Athenian naval power, though criticized and questioned, were put into effect. This naval power repulsed Xerxes' Persian forces and helped to prevent any wholesale influx of Eastern influence into the Hellenic world had the Persians been victorious, and secured the rise to prominence of the Athenian sea-state. Themistokles' efforts meant that Athens now stood as a military equal and consequent rival to Sparta, sowing the seeds for future confrontation, and the growth of Athens' merchant class and trade activities (aided by the leadership of the Delian League), was further secured by this superiority at sea.

Perikles' leadership of the Athenian people and the state, in contrast to Themistokles, was undisputed during the ten years of between early 443 when his rival Thucydides, the son of Melesias was ostracized, and the period of opposition against Perikles in 430. Perikles, like Themistokles, was a brilliant and capable politician, a patriot, and also a persuasive and convincing orator. Themistokles was certainly ambitious and an egoist, and this is also true for Perikles, however the ancient sources do not indicate as conclusively as they do for Themistokles that Perikles was prone to acts of deception and trickery to attain goals (as, for instance, in Plutarch’s allegation that Themistokles deceived the Spartans as a means of building the long walls around Athens).

Perikles' leadership of the Athenian people and the state, in contrast to Themistokles, was undisputed during the ten years of between early 443 when his rival Thucydides, the son of Melesias was ostracized, and the period of opposition against Perikles in 430. Perikles, like Themistokles, was a brilliant and capable politician, a patriot, and also a persuasive and convincing orator. Themistokles was certainly ambitious and an egoist, and this is also true for Perikles, however the ancient sources do not indicate as conclusively as they do for Themistokles that Perikles was prone to acts of deception and trickery to attain goals (as, for instance, in Plutarch’s allegation that Themistokles deceived the Spartans as a means of building the long walls around Athens).

Perikles' wide range of reforms indicated that he was a sincere democrat. Following the work of fellow democrat Ephialtes, Perikles played an important role in the creation of the radical democracy that Aristotle discussed in the Politics. He completed the democratization of the Athenian constitution by opening the archonship to the third class zeugitae, and in practice the fourth class thetes even gained entrance to the office (in about 457 B.C, though the dates for these reforms are unclear). In 451 B.C citizenship was restricted to those people whose parents were both Athenian citizens, and Perikles was responsible for the introduction of pay for public services for jurymen and for military service in 451. Perikles was also personally responsible for the lavish public works program that followed the transfer of the Confederacy of Delos to Athens, and he fostered a new wave of colonization and the establishment of cleruchies to Naxos, Andros, Thrace and Euboea, and also to Thurii in the West. Though the living standards of the private citizen in Periclean Athens were not necessarily raised, there was a marked improvement in commerce, consumer goods, community services and employment. One of Perikles' most significant accomplishments was the curtailing of the powers of the Areopagus and the Magistrates, which some commentators have even seen as a proletariat versus bourgeoisie triumph achieved by Perikles (though, it must be noted, Ephialtes also played a role in this development).

In Thucydides' account of Perikles' funeral oration in the first year of the Peloponnesian War, Perikles himself asserted that:

Our constitution is called a democracy because power is in the hands not of a minority but of the whole people.

The impact of such reforms was that Athens was at its prosperous peak during the period in political, military and cultural spheres, and the era was also marked by intellectual excellence in a number of fields.

While Perikles was never ostracized or exiled like Themistokles, he was removed from power for a time, despite his pre-eminent (and almost dictatorial) influence in 430, chiefly in opposition to his role in the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, his strategy for Athens in the early part of the conflict, and for the subsequent plague. Though Perikles may have had personal motivations for encouraging a war with Sparta (Diodorus Siculus suggests it was a means of avoiding rendering account of public moneys and Plutarch cites Perikles' ambition to overcome Athens' chief rival, Sparta), the sum impact of the conflict on the development of Athens was obviously critical and was one of the most significant events in all of Greek history.

While Perikles was never ostracized or exiled like Themistokles, he was removed from power for a time, despite his pre-eminent (and almost dictatorial) influence in 430, chiefly in opposition to his role in the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, his strategy for Athens in the early part of the conflict, and for the subsequent plague. Though Perikles may have had personal motivations for encouraging a war with Sparta (Diodorus Siculus suggests it was a means of avoiding rendering account of public moneys and Plutarch cites Perikles' ambition to overcome Athens' chief rival, Sparta), the sum impact of the conflict on the development of Athens was obviously critical and was one of the most significant events in all of Greek history.

Regardless, what is clear from a reading of Thucydides and Plutarch is that after Perikles died in 429 B.C, only then was the extent of Perikles' value and worth truly known as subsequent leaders attempted to succeed with different and more personally-motivated policies, and this was an important development in Athenian politics, particularly in diverting Athenian war strategy to other emphases. Whilst Perikles' rule stretched the very bounds of a true democratic leadership, he appears to have resisted any wholesale abuse of such powers. As Thucydides notes, Perikles "...could respect the liberty of the people and at the same time hold them in check."

Themistokles and Perikles were important figures in the development of Greek history. Themistokles, far more cunning and personally motivated than Perikles, ensured, showing foresight and thoughtfulness, that the appropriate reforms needed to facilitate Athenian naval predominance were implemented. Athenian naval power, combined with Themistokles' brilliant tactics, trickery, and sheer luck ensured the Persians were defeated at Salamis, which thus helped to prevent the immersion of Eastern culture and influence on the Hellenic world, and brought Athens to the fore in Greece, on a par with Sparta's power on land. Perikles, operating within the military and developing political framework which Themistokles and others had handed down, brought Athens into its 'Golden Age', encouraging even further democratic, economic and military development, and Athenian pre-eminence in Ancient Greece. That Athens' increased power and Perikles' own policies may have led Athens into war with Sparta meant that Perikles' career also marked the beginnings of the conflict which eventually brought Athens into defeat, even as the legacy of this period was the continued spread of Attic influence throughout Greece.

Themistokles and Perikles were important figures in the development of Greek history. Themistokles, far more cunning and personally motivated than Perikles, ensured, showing foresight and thoughtfulness, that the appropriate reforms needed to facilitate Athenian naval predominance were implemented. Athenian naval power, combined with Themistokles' brilliant tactics, trickery, and sheer luck ensured the Persians were defeated at Salamis, which thus helped to prevent the immersion of Eastern culture and influence on the Hellenic world, and brought Athens to the fore in Greece, on a par with Sparta's power on land. Perikles, operating within the military and developing political framework which Themistokles and others had handed down, brought Athens into its 'Golden Age', encouraging even further democratic, economic and military development, and Athenian pre-eminence in Ancient Greece. That Athens' increased power and Perikles' own policies may have led Athens into war with Sparta meant that Perikles' career also marked the beginnings of the conflict which eventually brought Athens into defeat, even as the legacy of this period was the continued spread of Attic influence throughout Greece.