- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

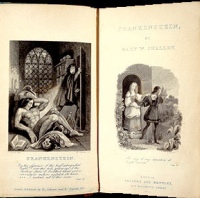

(Jan 2011) On Mary Shelley's 'Frankenstein' |

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) is profoundly modern and can be read in part as a parable about education, or more formally, about the relationship between the sexes.

The story is full of mutuality, familial harmonies, love and the desire for love, the desire to belong and be accepted, and the desire to participate in community, and the exemplification of the norms of beauty and handsomeness.

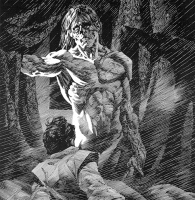

The story fully plumbs the horrors that emerge when one is excluded from those more harmonious and desired ‘norms’. While Frankenstein’s unnamed monster exemplifies brutalities, ugliness and evil, he does so in reaction to his own desires for a partner in love and companionship, and in reaction to his desire to participate in a human society that rejects him. In every sense, he does not fit in, and the human world elects to make no room for him and to define him only as the shunned monstrosity. In response he becomes an avenging nightmare and agent of death.

While Frankenstein’s unnamed monster exemplifies brutalities, ugliness and evil, he does so in reaction to his own desires for a partner in love and companionship, and in reaction to his desire to participate in a human society that rejects him. In every sense, he does not fit in, and the human world elects to make no room for him and to define him only as the shunned monstrosity. In response he becomes an avenging nightmare and agent of death.

Reading Frankenstein has caused me to reflect on aspects of a ‘gender in education’ debate set almost 200 years after that text. In some ways Frankenstein re-iterates aspects of Shelley’s late mother’s work – Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), which stated first and best something still driving modern education and the by now prominent place of women in that – at least in the liberal West.

One of the key motifs in Frankenstein (not by the way the name of the nameless monster, but of the monster’s creator) is found in Frankenstein’s final refusal to co-create a female companion for the male monster he has created. It is as alone and companionless, devoid of intimacy, that the monster becomes monstrous.

Frankenstein’s sub-creation asks Frankenstein to create a female of his own new species to be his companion. Frankenstein begins that work, but abandons it in fear of the consequences of a new race emergent. In gazing upon her half-formed form, he repents and destroys what he has begun to configure. He places her remains, or composite parts, in a basket and dumps this in the lake. The feminine will be absent from the world of the male as monster and in revenge, the monster kills Frankenstein’s bride on their wedding night. In some sense this action references the Greek Pandora, whose ‘All Gift’ is the unleashing of woes on the earth.

But Frankenstein had consigned the prior male creature, his own sub-creation anatomically and bio-chemically artificed with mystic scientific skill, to a terrible world of isolation, unloved-ness, vilified by every member of the human race that he encounters.

Frankenstein, the creator of life by impassioned science, becomes the wreaker of havoc by failing to complete his project and commit to the sub-creation of his own vision. He chickens out and creates instead a half-creature filled with violence, desire for retribution, and this monstrous, gigantic male is solitary and alone in the world.

This monster educates himself mimetically by observing harmless and kindly humans who remain unaware for a time of the alien amongst them.

In that time, we see this male isolate as a figure patent of good, who seeks company and friendship of inclusion.

But in fact the monster is a new Adam not of the human species but of a new species, different and effectively alien to the human race of men and women, and all humans, male or female, reject his overtures and flee from him in terror.

In return for the tainted gift of a partial and ugly and solitary creation, he begins to kill.

It is remarkable that Frankenstein, who can conjure (by his mystical passion and unheard of advanced science) a living form that is far more than a resuscitated composite corpse, something truly new and vital, cannot make something of enduring beauty and virtue, but only something that is seen as alien, ugly, evil, alone, male and brutish. He is then incapable of completing the female form to be a companion and co-equal.

Wollstonecraft, Shelley’s mother, had argued that both women and men in society as she knew it were damaged by the subjugation of ill-educated women to a life as mere ‘ornaments’ and appendages to an essentially male-dominated world of assumptions and domesticity and hierarchy. A world of mere manners and style, but lacking in learning and wisdom and mutuality. But not only were the women distorted by their exclusion from real education, the men were deformed by their lack of real, educated companions and life-ling friends and were as damaged. In some ways, Wollstonecraft’s women and men were themselves distortions, even monstrous.

Alienation between the sexes was the norm, and the remedy lay in commitment to the mutual education of women and men in each other’s company from early childhood – even allowing for differences of emphasis within a curriculum or method.

Education could not allow the opposite sex to become the null curriculum by virtue of an absence that itself creates the sense of alien others.

One can note the Frankenstein passages where this cry of pain of the male monster is profound. He is to be denied a female companion and he turns murderous and roams the earth as a dangerous loner until both he and Frankenstein perish in the far, icy North.