- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

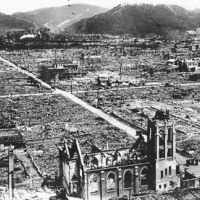

(Aug 2014) Hiroshima– Still Worth Remembering |

The events commemorating the centenary of the war of 1914-1918 have the potential to drown out other significant anniversaries. Surely the most hopeful interpretation of the centenary is that it will remind us of the destructiveness, inequity and futility of war. The best way to honour the sacrifices made by veterans of the 1914-18 war is to ensure that future generations do not endure similar fates. If this potential is to be fulfilled then amid the 1914-1918 events we should remember to reflect on the Hiroshima bombing on 6 August 1945.

The people of Japan learnt some hard lessons from Hiroshima. It is less than certain that the rest of the world learnt as much from that bombing and the later bomb at Nagasaki. Questions about whether atomic weapons should have been detonated in 1945 remain hypothetical or matters of belief: perhaps some lives were saved by the destruction of others; perhaps the demonstration of the horror of nuclear warfare helped to ensure that subsequently it would be considered a last resort; and maybe the Cold War remained cold because of the nuclear standoff between the then USSR and the USA.

Unfortunately, there are compelling reasons to think that the atomic bombing of Hiroshima left a tragic legacy not just for direct victims but for future generations. The calculation of lives saved and lives lost has become a ghoulish balance sheet. In discussions of the appropriate response to the Hussein dictatorship in Iraq for example, war proponents rejected the idea of moral equivalence between the deaths of children under the bombs of the Coalition of the Willing and their deaths under the dictator.

We seem to have accepted the possibility that killing can bring about good ends. Perhaps it is no surprise then that we care so little about the locking up of children and the state of their mental health. If we have already accepted that killing children can bring about something good, then of course we are prepared to visit lesser horrors on them. Before we can move on from a war, it is important to accept that our own killing is an evil to be overcome. It may be a necessity at the time but that is not the same as moral justification. We might do it, but that is in spite its evil nature. Killing is not imbued with positive morality because it has been forced on us.

The ‘victors’ in wars have a particular responsibility to avoid such justification. The nuclear age has been characterised by claims that we possess weapons only to deter attack. But we do not allow that others might take the same view. Our weapons are good – theirs are bad. The process of nuclear proliferation has been driven by the desire of some states to emulate the most powerful by acquiring nuclear capability. When the international community demands that Iran or India not join the ‘nuclear club’, the arsenals of the USA and USSR undermine these demands. It is possible too that the frequently reported domestic cynicism about government integrity is partly attributable to the lack of principle observed in international affairs. Governments can lie, obfuscate and act hypocritically or they can have moral authority, but not both.

National security is invoked to justify departures from normal behaviour. Citizens cannot be trusted in areas of knowledge beyond their understanding. Only governments understand what is going on. This paternalism means that power is dominated by forces which are technological and masculine. Trillions of dollars which might have been spent on ameliorating the causes of war have been wasted on research into defence shields like ‘Star Wars’ or on speculating about the possibility that earth’s elites might be able to move to another planet. Those with faith in technical solutions think that science will develop a solution to the problems of global warming and climate change. Elites do not wish to change their behaviour and feel threatened by calls to vary established economic patterns.

The belief in technology fits with other aspects of defence paradigms. It is not just a coincidence that the military exalts masculine values at the expense of the feminine. It is an active element in the subjugation of women. Women are more likely to seek personal approaches to all problem-solving, to take personal responsibility and to seek personal contact with issues or people perceived to be problematic. The difficulties experienced by women in the military - such as sexual harassment - are a direct result of masculine paradigms. The images of females in the Gaza conflict and indeed with a few notable exceptions in the aftermath of the Ukraine bombing are of tears, wailing and a status as defenceless victims. While women are represented as too emotional to be entrusted with high matters such as defence and foreign policy decisions, there has been little comment about the male domination of the circumstances which led to both tragic situations. Men and powerful weapons are a combination which threatens both not just the quality of life we can enjoy, but our very existence.

First World War centenary events will focus on heroism and sacrifice while hopefully, not neglecting the horror and the tragedy. There is nothing heroic in the Hiroshima story and nothing that could be mistaken as a cause for celebration. We must remember Hiroshima.

A former academic, Tony Smith has written extensively on a wide range of subjects as diverse as folk music and foreign policy issues in the Australian Review of Public Affairs, the Journal of Australian Studies Review of Books, Overland, the Australian Quarterly, Eureka Street, Online Opinion and Unleashed.