- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

The Cud On History: Shell Struck |

George Jumper of New Gloucester in Maine never forgot the moment the Death Angel came calling —

— and, fortunately, not for him.

Among the many Union monuments standing at Gettysburg, the bas relief monument dedicated to the First Maine Cavalry Regiment appears “alive” to Civil War buffs who traipse southeast along the Hanover Road to find East Cavalry Battlefield. Dedicated by survivors of the First Maine on October 3, 1889, the monument depicts a heavily armed cavalry trooper preparing to mount, left boot inserted in the stirrup and hands clasping saddle horn and horse mane.

Bursting three-dimensionally from a granite backdrop, the Maine trooper and his valiant steed gaze south across the Hanover Road, now a busy byway. Their eyes watch eternally for General J.E.B. Stuart and his Confederate cavalry — and those same eyes carefully “watch” every visitor who tromps around the monument. Those eyes, hollowed into the granite, “follow” the Mainer who stands below the horse’s nose or before the trooper to study the monument’s exquisite detail. The Mainer who moves a few feet left or right senses that horse and trooper observe that motion, because those eyes … if “haunts” occupy any particular Gettysburg monument or statue today, the First Maine Cavalry’s monument certainly qualifies.

History now obscures the specific First Maine trooper, if he existed, whose image the Gettysburg monument so carefully depicts. Candidates could include George E. Jumper, a New Gloucester resident assigned to Company G on May 28, 1864. A period photograph portrays a young, thin, and possibly short trooper with a moustache and a wispy beard. The granite trooper at Gettysburg seems older, perhaps wearied by countless hours spent in the saddle while battling Johnny Reb across Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

History now obscures the specific First Maine trooper, if he existed, whose image the Gettysburg monument so carefully depicts. Candidates could include George E. Jumper, a New Gloucester resident assigned to Company G on May 28, 1864. A period photograph portrays a young, thin, and possibly short trooper with a moustache and a wispy beard. The granite trooper at Gettysburg seems older, perhaps wearied by countless hours spent in the saddle while battling Johnny Reb across Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

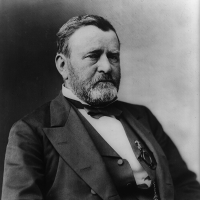

George Jumper, now a sergeant, and his Company G comrades rode forth on Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign in spring 1864. Appointed by President Abraham Lincoln as the Union Army’s commander-in-chief, Grant had devised a plan to batter the Confederates in Virginia. The Army of the Potomac, commanded by General George Meade of Gettysburg fame, would battle the Army of Northern Virginia, led by General Robert E. Lee. Simultaneously, another Union column would destroy the agricultural infrastructure in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, styled as “The Bread Basket of the Confederacy.”

Constantly skirmishing with Rebel cavalry and infantry, the First Maine Cavalry  accompanied Grant and Meade during that bloody spring. Yanks and Rebels slaughtered their opponents in the Wilderness and at Spotsylvania Courthouse as the opposing armies sidestepped southward, marching perpetually toward Richmond. Riding with General Phil Sheridan during an inglorious 17-day raid that netted many Yankee casualties and little strategic advantage, the First Maine boys reached Union lines on May 25.

accompanied Grant and Meade during that bloody spring. Yanks and Rebels slaughtered their opponents in the Wilderness and at Spotsylvania Courthouse as the opposing armies sidestepped southward, marching perpetually toward Richmond. Riding with General Phil Sheridan during an inglorious 17-day raid that netted many Yankee casualties and little strategic advantage, the First Maine boys reached Union lines on May 25.

A day later, Grant and Meade shoved the Army of the Potomac southward, this time across the Pamunkey River. On May 27, the First Maine’s hastily summoned troopers took their jaded horses over a pontoon bridge rigged by Meade’s expert engineers; Sergeant Jumper and his comrades settled down for a quiet spring evening.

Meanwhile, the Death Angel came seeking whom he could claim.

On May 28, the First Maine Cavalry deployed to protect a Union artillery battery blasting away at Confederate artillery near Hawes’ Shop, Virginia. Mary Renier Calvert, writing in her authoritative history, “The First Maine Cavalry,” noted that the Maine boys were “drawn up in line a short distance behind the [Yankee] battery,” a position that placed the mounted troopers definitively in the line of fire.

Rebel gunners had the distance. Lieutenant Edward P. Tobie, writing in his “History of the First Maine Cavalry” after the war, suggested that a tall chimney, almost the only component of a burnt house still standing, served as an aiming point for General Lee’s artillerymen. The First Maine boys were “watching the shot and shell strike the ground in their front … and all the time [were] wishing they were anywhere but there,” Tobie wrote.

Rebel gunners had the distance. Lieutenant Edward P. Tobie, writing in his “History of the First Maine Cavalry” after the war, suggested that a tall chimney, almost the only component of a burnt house still standing, served as an aiming point for General Lee’s artillerymen. The First Maine boys were “watching the shot and shell strike the ground in their front … and all the time [were] wishing they were anywhere but there,” Tobie wrote.

And with valid reason, because “a shell came bounding along the line from right to left” and shattered legs on three horses, which fell and dumped their riders. Its fuse sputtering, the shell stopped rolling beneath the horse bearing Major Jonathan Cilley. He applied the spur to his mount; both escaped injury.

The Death Angel came striding along the First Maine Cavalry’s lines. With so much iron and high explosive whizzing across the Virginia landscape, surely one Mainer would die today.

A while later, word reached Sergeant Jumper and his Company G comrades that they could dismount, a command they all appreciated because every Maine trooper and horse now made a smaller target. Calvert reported that Jumper “lingered by his saddle bags for a moment to get some tobacco.”

Hearing a Confederate cannon discharge, the Death Angel calculated the shell’s trajectory and whirled toward George Jumper. Stepping away from his horse, Jumper sat down. A second later, “a shell struck his horse in such a manner that, had he stood as he had only a moment before, or had he been on his horse, he would no doubt have been instantly killed,” Calvert recorded.

The shell killed the horse. Ignoring the Death Angel, which could only snap its bony fingers and mutter “aw, shucks,” George Jumper stripped his gear from his shattered mount, left everything with his comrades, and “left the field,” according to Calvert.

The shell killed the horse. Ignoring the Death Angel, which could only snap its bony fingers and mutter “aw, shucks,” George Jumper stripped his gear from his shattered mount, left everything with his comrades, and “left the field,” according to Calvert.

Jumper returned in about 30 minutes with another horse. “Then he gathered up his belongings, packed his saddle bags, and took his place in line as though nothing unusual had happened,” Calvert described the cool-under-fire Jumper.

The Death Angel did claim another Maine trooper that dangerous afternoon, but not George Jumper.