- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

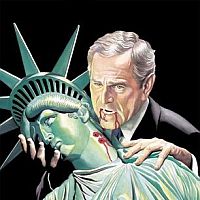

‘Anti-Democratic’ Behavior In Established Democracies (Or Why Kangaroo Courts, Torture and Detention Might Be Nothing New) |

One of the most distinct advantages of a comparative analysis between democracies — in this example, India, the United States and Japan — is that it  highlights certain common weaknesses within the theory and practice of democracy, irrespective of historical, cultural, or other factors. Indeed, during the democratic histories of India, the United States and Japan, each country has experienced a crisis in the strength of their democratic systems and its implied and expressed guarantee to protect individual human rights and freedoms, or to maintain a regular system of representative and participatory responsible government. Such ‘authoritarian’ or ‘anti-democratic’ behavior highlights the important distinction to be maintained between the need for the sovereignty of the individual versus the power and limits to be applied upon the state.

highlights certain common weaknesses within the theory and practice of democracy, irrespective of historical, cultural, or other factors. Indeed, during the democratic histories of India, the United States and Japan, each country has experienced a crisis in the strength of their democratic systems and its implied and expressed guarantee to protect individual human rights and freedoms, or to maintain a regular system of representative and participatory responsible government. Such ‘authoritarian’ or ‘anti-democratic’ behavior highlights the important distinction to be maintained between the need for the sovereignty of the individual versus the power and limits to be applied upon the state.

Faced with charges of electoral corruption during the Indian national elections of 1971 from which she was found guilty, and combined with a worsening domestic situation, on June 26, 1975, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared a national emergency and rushed through parliament dictatorial powers which she soon assumed, claiming that the emergency was needed to stabilize the crises facing the country, including famine, drought, and increased popular unrest and protest. Whilst Gandhi's broad powers and declaration of national emergency were, in theory, constitutionally valid as a means of suspending civil liberties if this would help to maintain the internal security of the country, she clearly acted undemocratically by imprisoning 676 political opponents a fortnight prior to passing the proposal for a national emergency declaration through parliament, thus  eliminating significant opposition. Irrespective of the fact that Indira Gandhi's ‘20-point program’ for improving the situation in India during the emergency brought some benefits, such as badly needed constitutional reform, improved consumer rights and stabilization of the economy, many of the improvements could have been implemented without any resort to censorship, dictatorial powers, and the centralization of power within the bureaucracy during this period. Though Indira Gandhi ended the emergency in 1977, the events of the period provide a dramatic example of how a constitutionally valid (and thus ‘democratic’) power may be used to undermine the rights and freedoms of individuals if the ‘national interest’ is asserted to be of most importance.

eliminating significant opposition. Irrespective of the fact that Indira Gandhi's ‘20-point program’ for improving the situation in India during the emergency brought some benefits, such as badly needed constitutional reform, improved consumer rights and stabilization of the economy, many of the improvements could have been implemented without any resort to censorship, dictatorial powers, and the centralization of power within the bureaucracy during this period. Though Indira Gandhi ended the emergency in 1977, the events of the period provide a dramatic example of how a constitutionally valid (and thus ‘democratic’) power may be used to undermine the rights and freedoms of individuals if the ‘national interest’ is asserted to be of most importance.

A similar example in the United States of democratic rights being overridden by the desire to protect the national good occurred during World War Two, when the internment of over 120,000 Japanese-Americans took place. The notable Louis Hartz thesis, The Liberal Tradition In America (1955) proposes that at various times during America's history, democracy has, under certain circumstances, become oppressive. Hartz suggests that since democracy is accepted by many without question in the United States, in times of undue stress, it is able to descend upon opposition because of its nature, and because of its unthinking liberal ideology. Arising out of the paranoia which gripped much of white America in the  aftermath of the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, growing fears of a renewed and rabid Japanese imperialism encroaching upon the United States began to spread, and when combined with pre-existing racist attitudes and beliefs, President Roosevelt was prompted under pressure to sign Executive Order 9066, which designated ‘military areas’ on the West Coast of America which were to be evacuated by all those persons who were perceived to be potential threats to the safety of the nation. No attempts were made to distinguish between the supposedly ‘loyal’ or ‘disloyal’ Japanese, and those who were evacuated were soon placed in concentration camps across the country. When the camps were closed at the end of 1945 it was not until a full fifty years later that complete restitution was extended to those whose civil liberties — many of them Japanese American citizens — had been so unfairly violated. The internment affected the lives of all Japanese-Americans, and not only destroyed their faith in the democratic ideology, but it proved that in times of war in the United States the first casualty of war is not necessarily truth, but democracy itself.

aftermath of the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, growing fears of a renewed and rabid Japanese imperialism encroaching upon the United States began to spread, and when combined with pre-existing racist attitudes and beliefs, President Roosevelt was prompted under pressure to sign Executive Order 9066, which designated ‘military areas’ on the West Coast of America which were to be evacuated by all those persons who were perceived to be potential threats to the safety of the nation. No attempts were made to distinguish between the supposedly ‘loyal’ or ‘disloyal’ Japanese, and those who were evacuated were soon placed in concentration camps across the country. When the camps were closed at the end of 1945 it was not until a full fifty years later that complete restitution was extended to those whose civil liberties — many of them Japanese American citizens — had been so unfairly violated. The internment affected the lives of all Japanese-Americans, and not only destroyed their faith in the democratic ideology, but it proved that in times of war in the United States the first casualty of war is not necessarily truth, but democracy itself.

In the Japanese democratic experience, concerns have been raised regarding the one-party dominance in politics since 1955 by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). The primary issue, as forwarded by commentators such as J.A.A. Stockwin, is that the prolonged rule of the LDP in Japan may have come at the expense of political development and progress, as the repeated re-election of the party may have  fostered a decline in the ‘dynamic’ decision-making and ideas needed to uphold a system of responsible ‘good government’. Another concern of the LDP has been that whilst in power for several decades, it gradually internalized all of the debate, competition and policy-related argument associated with parliamentary government, so that although this democratic process was still being fulfilled within the party, the opportunities for popular or party contribution and participation in political debate were limited. Whilst, in truth, it appears unlikely that the dominance of the LDP has been of a completely ‘undemocratic’ nature since there has been a continued opportunity for varied representation, alternating governments, and voter's choices have generally reflected those who are in power, the Japanese experience is of value in this discussion since it highlights a possible weakness in the democratic system that may arise- that an elected party may rule for an extended period simply because there is little organized or effective opposition, the ruling party may be better financed or resourced than others, or because the citizenry simply becomes lax in its voting; accustomed to rule by one party for several years.

fostered a decline in the ‘dynamic’ decision-making and ideas needed to uphold a system of responsible ‘good government’. Another concern of the LDP has been that whilst in power for several decades, it gradually internalized all of the debate, competition and policy-related argument associated with parliamentary government, so that although this democratic process was still being fulfilled within the party, the opportunities for popular or party contribution and participation in political debate were limited. Whilst, in truth, it appears unlikely that the dominance of the LDP has been of a completely ‘undemocratic’ nature since there has been a continued opportunity for varied representation, alternating governments, and voter's choices have generally reflected those who are in power, the Japanese experience is of value in this discussion since it highlights a possible weakness in the democratic system that may arise- that an elected party may rule for an extended period simply because there is little organized or effective opposition, the ruling party may be better financed or resourced than others, or because the citizenry simply becomes lax in its voting; accustomed to rule by one party for several years.

Evidence of authoritarian and anti-democratic behavior has clearly taken place, therefore, in the democracies of India, the United States and Japan. Whilst the accusation of undemocratic one-party rule in Japan is a serious one, it is the overt restrictions upon democratically guaranteed civil liberties in India and the United States that have served to clarify the existence of several  important weaknesses in the democratic ideology; most particularly that at various times a democratic country may deem it unacceptable for individuals in society to break away from the ‘national interest’, and that the importance of the nation-state may therefore presume the subordination of individual rights and freedoms. Above all, the persistence of such recognizable flaws in the experiences of three diverse democracies suggests that it is the theoretical inability of democracy to reconcile satisfactorily the role of the individual and the state, and not the historical experiences, wealth, cultural background, or other such factors that will necessarily always determine the effective operation of a democratic regime.

important weaknesses in the democratic ideology; most particularly that at various times a democratic country may deem it unacceptable for individuals in society to break away from the ‘national interest’, and that the importance of the nation-state may therefore presume the subordination of individual rights and freedoms. Above all, the persistence of such recognizable flaws in the experiences of three diverse democracies suggests that it is the theoretical inability of democracy to reconcile satisfactorily the role of the individual and the state, and not the historical experiences, wealth, cultural background, or other such factors that will necessarily always determine the effective operation of a democratic regime.