- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

Walking The Thin Line To Liberty: The American Soldier and the role of Civil Disobedience |

The Iraq War of 2003 was unusual in many respects, one being the huge opposition worldwide before it had even begun. An estimated 36 million people demonstrated their disapproval in the  months surrounding the beginning of the invasion1. For those who might believe that democratic governments are always interested in the opinions of people, it might be worth remembering the comments of a high-ranking former member of the U.S. administration: Paul Wolfowitz. Faced with Turkey’s decision to follow the will of 95% of its population and refuse Washington access to open a front into Iraq from Turkey, the response was swift from the U.S. media and the U.S. government. Turkey “lacked democratic credentials”. Wolfowitz was more fanatical, expressing disbelief that the Turkish military had not forced the government to follow the Washington line. The Turkish military should admit their mistake and “figure out how to be as helpful as possible to the Americans”2.

months surrounding the beginning of the invasion1. For those who might believe that democratic governments are always interested in the opinions of people, it might be worth remembering the comments of a high-ranking former member of the U.S. administration: Paul Wolfowitz. Faced with Turkey’s decision to follow the will of 95% of its population and refuse Washington access to open a front into Iraq from Turkey, the response was swift from the U.S. media and the U.S. government. Turkey “lacked democratic credentials”. Wolfowitz was more fanatical, expressing disbelief that the Turkish military had not forced the government to follow the Washington line. The Turkish military should admit their mistake and “figure out how to be as helpful as possible to the Americans”2.

Despite unprecedented protests, the war went ahead. The mainstream press adopted the gung-ho government line initially, but has become more critical as the situation has deteriorated. A lot of this criticism has been well reasoned and persuasive. For the most part, criticism has been of strategy – whether the war has contributed to the so-called War on Terrorism (TWOT), whether Iraqi people are somehow better off and whether it was worth spending all that money to rid the world of the tyrant, Saddam Hussein, and so on. Some have questioned the war’s legality within international law. A few, the usual suspects, have even broached the normally taboo issue of the ethics of our own actions, daring to suggest that perhaps it may have been an immoral act, not merely an illegal or unwise one. But this has been confined almost completely to the alternative media.

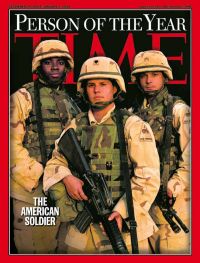

What there has not been much criticism of are the soldiers themselves. Time Magazine’s Person of the Year in 2003, the American soldier, (President G.W. Bush was Person of the Year in 2004 – this was the second  time for both)3, has been lauded for bravery and competence in helping the U.S. government achieve its purported humanitarian objectives. Why are the government and its officials open to criticism, but the soldier, effectively someone paid to kill when the government orders it to, immune from reproach?

time for both)3, has been lauded for bravery and competence in helping the U.S. government achieve its purported humanitarian objectives. Why are the government and its officials open to criticism, but the soldier, effectively someone paid to kill when the government orders it to, immune from reproach?

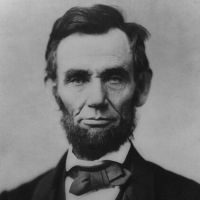

If history is anything to judge by, claims of noble intent by governments or their supporters should give us immediate pause. Whether it is Mill’s essay on Humanitarian Intervention4, justifying English intervention and expansion in India, the Japanese “humanitarian assistance” of Manchuria, or Hitler’s “humanitarian intervention” in Czechoslovakia5, the morality of an action is determined by the facts of the circumstances, not by righteous declarations. Likewise, soldiers are not worthy of respect a priori — Do Al Qaeda’s soldiers deserve praise by virtue of the fact that they are soldiers? Naturally not: the facts of the situation determine the aggressors and the victims. Politicians, credulous journalists and others are not above distorting events to achieve support, even as no doubt some of this is quite sincere. The romantic image of soldiers sacrificing themselves for the freedom of others is powerful, and like a lot of rhetoric, prone to distract people from real events. Abraham Lincoln perhaps captured this most eloquently when referring to the eagerness of President Polk during the Mexican War:

Trusting to escape scrutiny, by fixing the public gaze upon the exceeding brightness of military glory – that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood – that serpent’s eye, that charms to destroy – he plunged into war6.

The Mexican War, in what should now have become familiar, was also characterised to the American people as a war of self-defence. The dominant mythology of the Vietnam War, to take another example, is one of the victimisation of the U.S. at the hands of the Vietnamese. The U.S. Army was acting in self-defence on foreign soil. The similarity with the situation in Iraq is revealing. Criticism of Vietnam amounts to discussion of strategy, questioning of resources spent. Little mention is made of the suffering visited upon the Vietnamese just as there is scant attention paid to the numbers of Iraqi dead. The disproportion between these alleged threats to national security barely raises an eyebrow within local circles. People outside the sphere of the propaganda may interpret things differently. When Kennedy wished to include Mexico in its terrorism against Cuba because of the perceived threat to the U.S.’s security, the Mexican ambassador responded dryly “… if we publicly declare that Cuba is a threat to our [Mexico’s] security, forty million Mexicans will die laughing”7. Or perhaps you recall Reagan resolutely holding back the hordes of terrifying Grenada, bravely invading after refusing offers of a peaceful settlement on  U.S. terms8? Propaganda is just one of the tools that governments or other powerful interests can use to distort information or distract the public from actions that they may find unwise or even immoral. Nationalism and rhetoric inflame passions, drawing us away from facts and impartiality. We become blind or tolerant to the crimes of our own government and have diminished sympathy, if any recognition at all, of other people and their rights. Playing on the public’s fears — having people believe that they are under constant threat – also persuades people to surrender certain rights and avoid questioning the authority of the government. Despite these techniques designed to cloud and distract, definitions of aggression are well understood, both from the UN Charter and from legal precedents such as the Nuremburg Trials. Aggression and subsequent responsibilities can be determined by a legal process — that is, for those that wish to be a part of the international community and not above it.

U.S. terms8? Propaganda is just one of the tools that governments or other powerful interests can use to distort information or distract the public from actions that they may find unwise or even immoral. Nationalism and rhetoric inflame passions, drawing us away from facts and impartiality. We become blind or tolerant to the crimes of our own government and have diminished sympathy, if any recognition at all, of other people and their rights. Playing on the public’s fears — having people believe that they are under constant threat – also persuades people to surrender certain rights and avoid questioning the authority of the government. Despite these techniques designed to cloud and distract, definitions of aggression are well understood, both from the UN Charter and from legal precedents such as the Nuremburg Trials. Aggression and subsequent responsibilities can be determined by a legal process — that is, for those that wish to be a part of the international community and not above it.

No doubt part of the sense of the mitigated culpability of soldiers is that they are following orders, that it is in the nature of their job that they follow orders without question and that they are removed from the decision-making process. The Nuremburg Defence is this argument. In the Nuremburg Trials, under the Nuremburg Principles, however, this is not sufficient to exonerate those accused of war crimes, although it might lead to lighter sentencing. The American psychologist Stanley Milgram’s controversial experiments on obedience to authority demonstrate the willingness of most subjects to commit hurtful acts when ordered to do so by an authority figure9. 26 out of 40 participants in the experiment inflicted what they believed to be a 450 Volt electric shock 3 times on another volunteer, despite screams of pain and pleas to stop, when ordered by the authority figure to continue. Few challenged the authority figure and the challenges were limited although many of the participants were clearly stressed by the circumstances. Thus it will come as no surprise if few soldiers, situated in a work environment so strongly grounded in authority, will seek to challenge officers even if they disagree with orders or believe them to be immoral.

Certainly, there are different degrees of complicity in immoral acts. The person who orders the war crime  to be committed, the person who follows orders to commit it, the person who is aware of it, but does nothing — these people have different levels of involvement. All these people are nevertheless participants of a kind, and with participation comes responsibility. Being a nice slave owner who cares for one’s slaves does not alter the fact that slavery as a system is abhorrent and that participation in an immoral act, involves implication of some degree, taking into account the circumstances.

to be committed, the person who follows orders to commit it, the person who is aware of it, but does nothing — these people have different levels of involvement. All these people are nevertheless participants of a kind, and with participation comes responsibility. Being a nice slave owner who cares for one’s slaves does not alter the fact that slavery as a system is abhorrent and that participation in an immoral act, involves implication of some degree, taking into account the circumstances.

Looking at the case of a soldier is instructive because soldiers play a more direct role in aggression and because of the hierarchy of the system. Targeting soldiers alone is unfair. For the most part in the U.S., the fighting is done by the lower classes. The mythology surrounding the soldier functions not only to encourage obedience and nationalism, but also to prevent class resentment; the poor people do most of the dying for the interests of the wealthy10. Most of the soldiers need their job to put food on the table. It is harder to take a moral stand about decisions you might disagree with when it might threaten your livelihood.

Almost all of us participate in the State to some extent. We pay taxes. We receive certain benefits: an education system, a fire brigade and so on. We may take part in the electoral process as it stands. If the State is guilty of breaking certain laws, or more importantly is engaging in immoral undertakings, then to be aware of it and offer assistance to the State to carry out such acts is an act of implication to some extent. This motivated Henry David Thoreau to write “Civil Disobedience” and also to spend a night in jail for refusing to pay taxes on the grounds that he did not want to support a government involved in the Mexican War and slavery:

It is not a man’s duty, as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous, wrong; he may still have properly have other concerns to engage him; but it is his duty, at least, to wash his hands of it, and, if he gives it no thought longer, not to give it practically his support.

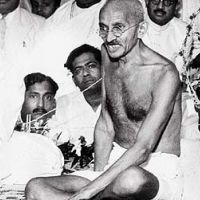

Not all laws are just laws and require our obedience. Citizens owe allegiance to ethics before the laws of  the land. Indeed, civil disobedience can be an important trigger for social change. Rosa Parks, in refusing to give up her seat on a bus in 1955, made an important contribution to the American Civil Rights Movement. Mahatma Gandhi, influenced by Thoreau’s essay, formulated his own rules for a system of civil disobedience, satyagraha, involving Hindu principles of non-violence, ahimsa. The U.S. Declaration of Independence itself captures the rights and responsibilities of a just government. To quote Zinn’s perception of true patriotism:

the land. Indeed, civil disobedience can be an important trigger for social change. Rosa Parks, in refusing to give up her seat on a bus in 1955, made an important contribution to the American Civil Rights Movement. Mahatma Gandhi, influenced by Thoreau’s essay, formulated his own rules for a system of civil disobedience, satyagraha, involving Hindu principles of non-violence, ahimsa. The U.S. Declaration of Independence itself captures the rights and responsibilities of a just government. To quote Zinn’s perception of true patriotism:

Government is set up … by the people in order to fulfil certain responsibilities: equality, life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness. And when, according to the Declaration of Independence, the government violates those responsibilities, then … it is the right of the people to alter or abolish the government … The government is not to be obeyed when the government is wrong11.

Surprisingly, recent action against the State in the form of sabotage and other acts of civil disobedience has found some support in the courtroom. Certain rulings in European courtrooms have sounded warnings to governments that their power resides in the people and, as such, can be taken away. Activists in England who had broken into military bases and damaged equipment argued that they were trying to prevent war crimes from being committed. The charges were serious – conspiracy to commit criminal damage, carrying a possible penalty of 10 years – but the jury failed to reach a verdict. George Monbiot offers other similar examples that have yielded similar results12. Citing other English laws such as section 3 of the 1967 Criminal Law Act, allowing for “a person … [to] … use such force as is reasonable in the prevention of a crime”, has allowed legal leverage to the activists. Non-verdicts do not carry any legal obligation, but they do weaken the authority of the government to force convictions on such matters.

As to what constitutes valid civil disobedience, we can make such judgements although they may be tentative as situations and knowledge allow. Given that we are responsible for the predictable consequences of our actions, but not those that are unpredictable, then certain acts may be undertaken with good intentions but have undesirable consequences. They can be “legitimate in principle, though improper in social consequence”13. Actions undertaken to limit the power of an agency to commit crimes or to bring awareness of these crimes to more people are actions promoting justice.

As to what constitutes valid civil disobedience, we can make such judgements although they may be tentative as situations and knowledge allow. Given that we are responsible for the predictable consequences of our actions, but not those that are unpredictable, then certain acts may be undertaken with good intentions but have undesirable consequences. They can be “legitimate in principle, though improper in social consequence”13. Actions undertaken to limit the power of an agency to commit crimes or to bring awareness of these crimes to more people are actions promoting justice.

In the final assessment there is one clear conclusion that demands our attention: It is up to us to hold our governments accountable. One brave individual challenging authority offers inspiration to many.

People should not be afraid of their governments. Governments should be afraid of their people15.

Endnotes:

- Dominique Reynié, cited in Anti-war protests do make a difference, Alex Callinicos, Socialist Worker, 19 March 2005.

- Noam Chomsky, Failed States, Metropolitan, 2006, p133.

- It should be noted that being the Person of the Year is not an honour as such, but indicates influence for that year.

- J.S. Mill, "A Few Words on Non-Intervention," Fraser's Magazine, December 1859

- These examples were found in “Europe and America as Underwriters of the International Order” a transcript of a talk that can be found online at: http://www.chomsky.info/talks/20060119.htm

- Those wishing more comprehensive references to these should check Chomsky’s Failed States, pp 104-6.

- This quote of Lincoln’s is taken from Kurt Vonnegut’s A Man Without a Country, Random House, 2007, p 76. For an account of the Mexican War (and all recent U.S. history) it is hard to ignore Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, Harper Perennial, 2003, especially pp 152-69.

- Noam Chomsky, Hegemony and Survival, Allen and Unwin, 2004, p 87. Pages 80-90 give a detailed account of U.S. terrorism against Cuba.

- Noam Chomsky, Necessary Illusions, South End Press, 1989, pp 176-80. A full copy of this can be found online here: http://www.zmag.org/chomsky/ni/ni.html

- Stanley Milgram Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View, HarperCollins, 1974. This is nothing new, but it is hard to resist a quote from James Mellon’s father giving advice to his son, one of the wealthy to pay $300 to avoid service in the U.S. Civil War: “a man may be a patriot without risking his own life or sacrificing his health. There are plenty of lives less valuable.” Zinn, Op. Cit., p 255.

- This is taken from an online transcript of a talk given on Patriot’s Day in Boston, 2007. The transcript, dated 16/4/07 is available here: http://www.democracynow.org/article.pl?sid=07/04/16/1338223&mode=thread&tid=25

- George Monbiot, “Putting the State on Trial”, which can be found online here: http://www.monbiot.com/archives/2006/10/19/putting-the-state-on-trial/

- This is a paraphrase of a point that Noam Chomsky makes in “On the Limits of Civil Disobedience”, found in For Reasons of State, The New Press, 2003, p 295.

- This is a quote from the movie “V For Vendetta”. It is sometimes taken to be a paraphrase of Thomas Jefferson’s, but the Jefferson Library denies this.