- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

Democracy, Dictatorships… Or Both? Assessing Ancient Athens’ Great Statesmen |

In theory, democratic Athens implied power based upon majority support, and therefore an  end to tyranny and dictatorial powers for the leaders of Athens. In practice, however, the experiences of such important Athenian statesmen as Kimon, Perikles and Alkibiades were marked by the possession of considerable power in the hands of a few political rivals, or in the hands of one undisputed leader, as occurred in the example of Perikles. This peculiar situation suggests that within fifth century Athens the prevailing system, undergoing constant change and still in a relatively early form of 'true' democracy as we know it today, still allowed certain influential leaders to rise to predominance because of the emphases on securing support of the demos for political actions, and because of the Athenian's reliance upon strong leaders to maintain the security of Athens and assert her predominance in Ancient Greece.

end to tyranny and dictatorial powers for the leaders of Athens. In practice, however, the experiences of such important Athenian statesmen as Kimon, Perikles and Alkibiades were marked by the possession of considerable power in the hands of a few political rivals, or in the hands of one undisputed leader, as occurred in the example of Perikles. This peculiar situation suggests that within fifth century Athens the prevailing system, undergoing constant change and still in a relatively early form of 'true' democracy as we know it today, still allowed certain influential leaders to rise to predominance because of the emphases on securing support of the demos for political actions, and because of the Athenian's reliance upon strong leaders to maintain the security of Athens and assert her predominance in Ancient Greece.

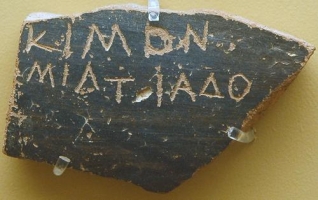

Kimon, the son of Miltiades served in the Persian Wars with considerable success, and had advanced in politics as a protégé of Aristides, and at a time when public support for Themistokles had fallen. Between 472 and 461 he was one of the most popular, influential and powerful men in Athens, he was repeatedly elected as one of the ten strategoi, and he led the Delian League forces from 478 to 461, though initially he was only League fleet leader. His greatest success came in 468 when he was victorious over the Persian forces at Eurymedon. Kimon's popularity and strong leadership was apparent in 463 when the people successfully overturned charges of bribery against him that had been made by  Perikles and other members of the democratic faction, however in 461 he was ostracized for his pro-Spartan sentiments. When Kimon was recalled in 450 he negotiated a peace between Athens and Sparta but he died in the same year whilst on expedition to Cyprus.

Perikles and other members of the democratic faction, however in 461 he was ostracized for his pro-Spartan sentiments. When Kimon was recalled in 450 he negotiated a peace between Athens and Sparta but he died in the same year whilst on expedition to Cyprus.

Kimon's policy was to maintain the dual hegemony of Athens' supremacy at sea, and to recognize the supremacy of Sparta on land, and yet, whilst he was a strong and powerful leader in democratic Athens, he was also aristocratic and a conservative. His career illustrates how democratic Athens had allowed his leadership, but that when his political stance was presented to the people (by such individuals as Ephialtes and Perikles) as being contrary to the interests of democracy, his ostracism was secured and his influence in Athens never fully recovered from the trauma as the democrats were able to implement a number of reforms which undermined the position of his conservative party.

Despite Perikles' radical and popular democratic reforms, Thucydides suggests that in Athens under Perikles, "...in what was nominally a democracy, power was really in the hands of the first citizen". Indeed, Perikles seems to have dominated Athens and enforced his rule when we consider his long-term leadership. Between 467 and 428 B.C Perikles was almost continually elected as one of the ten strategii. The additional position of strategos "ex apanton" (virtually equivalent to a constitutional dictator) was created during the rule of Perikles to overcome the difficulties of his continuous tenure as a strategos (though it has been argued- most especially by K.J Dover that the ten strategoi were roughly equal in power).

The predominance of rivals such as Ephialtes, Leokrates, Myronides, Kimon, Tolmides, and most significantly, Thucydides, the son of Melesias seem to have prevented Perikles' complete domination of Athens in the earlier period of his career; and his brief fall from power in 430 and indications of opposition to both him and his policies in the 430's suggest that Perikles still had to convince the assembly of the soundness of every proposal that he put forward.

The predominance of rivals such as Ephialtes, Leokrates, Myronides, Kimon, Tolmides, and most significantly, Thucydides, the son of Melesias seem to have prevented Perikles' complete domination of Athens in the earlier period of his career; and his brief fall from power in 430 and indications of opposition to both him and his policies in the 430's suggest that Perikles still had to convince the assembly of the soundness of every proposal that he put forward.

Plutarch states, however, that after Thucydides' ostracism, when Perikles' pre-eminence was largely assured, that his own conduct took on a different character:

"...Since he used his authority honestly and unswervingly in the interests of the city, he was usually able to carry the people with him by rational argument and persuasion. Still there were times when they bitterly resented his policy, and then he tightened the reigns and forced them to do what was to their advantage..."

Perikles was able to operate within the democratic system of Athens with very broad powers, and in a position of strong leadership. It is therefore critical to recognize that whilst Perikles came to power as leader of the Demos, the unpropertied, as soon as Perikles was free from his rivals, and when nothing further was lacking to his monarchical power, he by no means wanted to push the bounds of extreme democracy any further. He had no intention of allowing rule by a class or to suppress that class from which he himself had come. Rather, he hoped to reconcile the educated and wealthy circles of the citizenry with the new order of things, and to show that the unlimited rule of the masses was not equated with  anarchy and that property could still be protected by the same guarantee as before. He was fortunate in this endeavor to have access to the huge finances of the state treasury, which kept the mob's demands happy without needing to take away from the rich for that purpose.

anarchy and that property could still be protected by the same guarantee as before. He was fortunate in this endeavor to have access to the huge finances of the state treasury, which kept the mob's demands happy without needing to take away from the rich for that purpose.

Although the democratic model which Perikles discussed in his funeral oration of 431/0 B.C was not always so successful in practice, and even as several of the ancient sources evidence the predominant position which he maintained, the vast undertaking of Perikles' reforms and their significant long-term impact indicate that overall Perikles seems to have been a genuine democrat with a genuine program for the development of the radical democracy, and this is what allows Perikles to stand distinct in this period from other strong leaders of his time. Perikles' rule stretched the very bounds of a true democratic leadership, and yet he appears to have resisted any wholesale abuse of such powers; rather than destroy the heart of democracy, Perikles' pre-eminence in such a relatively early stage of the development of radical democracy in fact kept the recently deposed tyrants out of power, and as Thucydides commented, his rule truly operated in this sense, therefore, as "...the saving bulwark of the state."

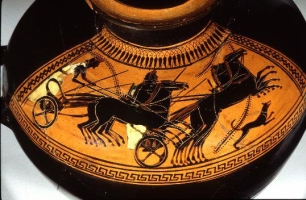

Whilst Alkibiades' career was certainly more erratic than that of Perikles and Kimon by nature of his shifting allegiances, he still represents an example of an individual that was able to secure strong leadership and have many of his plans implemented merely by his power to sway the support of the demos, especially against his chief rival, Nikias. Alkibiades' interpretations of 'honor' and the example set by his private life were certainly different to the more conservative Nikias (and obviously an individual such as Perikles), and thus it is remarkable that in the debates concerning the Sicilian expedition of 415 B.C he was able to convince the assembly of the viability of his doomed plan. Alkibiades, along with Nikias and Lamachus was placed in command of the ambitious expedition. Plutarch tells us that Alkibiades was a very talented speaker, and he certainly used the power of oratory to rise to power and secure his position in Athens.

After Alkibiades' retreat to Sparta in August/September 415 B.C in light of the charges  against him concerning the mutilation of the Hermae, and after his subsequent maneuvers in Persia, it is perhaps surprising that the Athenian state allowed for his return in 411 after Alkibiades showed such swaying allegiances away from democratic Athens (even to the point of having supported the oligarchic faction in Athens in the winter of 412-411 B.C). Throughout his career Alkibiades certainly showed he was not a sincere democrat: from 415 to 410 he posed as an advocate for oligarchy, and after 410 he was champion of democracy. Alkibiades' true loyalties lay with himself first and foremost, and consequently with his own survival. Though his next loyalty was with Athens, when Athens was alienated by Alkibiades' behavior he looked elsewhere to maintain his political career and to save his ambitions. Whilst it is debatable as to whether Alkibiades actually had any personal aims to set up a tyranny in Athens, the mere fact that he was given the position of 'strategos autocratos' in 408 -the granting of absolute powers over both land and sea- after his previous actions may suggest to us that democratic Athens was, if not actually favorable, certainly accommodating to strong leadership when it was in need of it, especially in light of Alkibiades' military successes as at Cyzicus in 410. Alkibiades only held the position of strategos autocratos briefly due to the defeat at Ephesus in 407, however, which suggests the conclusion that even amidst a powerful leader in Athens the system still was capable of placing restrictions upon individual statesmen (as, in this instance, the assembly was turned against Alkibiades by the slanders of Thrasybulus).

against him concerning the mutilation of the Hermae, and after his subsequent maneuvers in Persia, it is perhaps surprising that the Athenian state allowed for his return in 411 after Alkibiades showed such swaying allegiances away from democratic Athens (even to the point of having supported the oligarchic faction in Athens in the winter of 412-411 B.C). Throughout his career Alkibiades certainly showed he was not a sincere democrat: from 415 to 410 he posed as an advocate for oligarchy, and after 410 he was champion of democracy. Alkibiades' true loyalties lay with himself first and foremost, and consequently with his own survival. Though his next loyalty was with Athens, when Athens was alienated by Alkibiades' behavior he looked elsewhere to maintain his political career and to save his ambitions. Whilst it is debatable as to whether Alkibiades actually had any personal aims to set up a tyranny in Athens, the mere fact that he was given the position of 'strategos autocratos' in 408 -the granting of absolute powers over both land and sea- after his previous actions may suggest to us that democratic Athens was, if not actually favorable, certainly accommodating to strong leadership when it was in need of it, especially in light of Alkibiades' military successes as at Cyzicus in 410. Alkibiades only held the position of strategos autocratos briefly due to the defeat at Ephesus in 407, however, which suggests the conclusion that even amidst a powerful leader in Athens the system still was capable of placing restrictions upon individual statesmen (as, in this instance, the assembly was turned against Alkibiades by the slanders of Thrasybulus).

What emerges from an analysis of the careers of Kimon, Perikles and Alkibiades,  therefore, is that the history of democratic Athens was marked by strong individual leaders wielding considerable power. It is critical to recognize that this power, broad as it was for someleaders, always operated within the framework of the democracy, and thus each of the leaders fell prey at some point during their careers to the decisions of the assembly, the courts, or to the method of ostracism. The safeguards of the democratic system still checked even the most powerful leaders in Athens, and thus while strong leaders may have prevailed in the period, particularly in times of crisis, all statesmen in Athens were ultimately restricted by the devices of the system against complete tyranny and dictatorial rule.

therefore, is that the history of democratic Athens was marked by strong individual leaders wielding considerable power. It is critical to recognize that this power, broad as it was for someleaders, always operated within the framework of the democracy, and thus each of the leaders fell prey at some point during their careers to the decisions of the assembly, the courts, or to the method of ostracism. The safeguards of the democratic system still checked even the most powerful leaders in Athens, and thus while strong leaders may have prevailed in the period, particularly in times of crisis, all statesmen in Athens were ultimately restricted by the devices of the system against complete tyranny and dictatorial rule.