- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

The Cud On The Road- |

Mahoosuc Notch was a natural bottleneck, so we mustered at its entrance. After 2,000 miles of opportunities to spread out and lose each other, seven Appalachian Trail thru-hikers, myself included, converged in the Maine woods at this, the toughest mile of the nation's flagship long distance footpath. One mile, one hour. One mile per hour.

We all had something in common: the right stuff. The herd of hikers who roamed the southern Appalachian Mountains months earlier like bewildered pack animals not knowing what to do without the safety of the herd, had thinned and evolved into a new animal. Sleek, purposeful, independent, we gathered for simple camaraderie.  This new animal didn’t travel in a herd. Cattle travel in a herd; wolves in a pack; emus in a mob; and fish in a school. Thru-hikers travel in a funk.

This new animal didn’t travel in a herd. Cattle travel in a herd; wolves in a pack; emus in a mob; and fish in a school. Thru-hikers travel in a funk.

Our funk of thru-hikers was at the verge of Mahoosuc Notch. The Notch is what you would expect to find if a giant put its shoulder through a mountain, in order to make a shortcut from one side to the other. The granite walls of this new shortcut collapsed and settled onto the terra nova below. The result is a lot of texture—obstacles of a large scale. In addition to being the toughest mile on the Trail, it is also the most gymnastic.

I was known then as Dirty and Deranged, Double D for short. That’s a long story. I arrived first, as I had planned to, because I always appreciated scenery more when it was free of people. I was a bit of a recluse within the A.T. community, which is really saying something. But I was merely attracted to the fleeting scenes of wilderness that were more difficult to find than I would have thought.

As usual that morning, I had my stomach on my mind. I barked back at The Rumble, “Settle down, we just had breakfast. And we’re having Hamburger Helper tonight, with tuna.” Everything was with tuna. Right then I found a piece of last night’s tuna in my beard and moistened it on my tongue before swallowing it. You gotta’ understand, at that point my body could have swallowed crude oil but pissed out jet fuel.

The path I saw before me looked like it would descend into the center of the Earth. A clever person could post a sign saying, “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.” But then other people, neither clever nor funny, would call it litter and take it down. But I wouldn’t mind.

The physical, earthen trail simply ceased when the conceptual trail continued past a drop in the landscape into the boulder-laden ravine that was our pathway. It hardly mattered, we all knew the Trail came out the other side of this crack in the Earth.

Jackaroo was next to arrive. Jackaroo was from backwater Florida. His name was drawn from the term for an Australian stockman, which made absolutely no sense except that the name actually was bestowed on him by an Aussie hiker. He pulled his sweaty black shirt from his chest, took one look over my shoulder into the Notch and said, “Sheeeeiitttt.” Then he took off his blue head band and shook the sweat from his greasy black hair.  This repelled his attendant militia of mosquitoes to a safe distance, where they hovered spread out like a starry night before collapsing back into a nebulous cloud around his head.

This repelled his attendant militia of mosquitoes to a safe distance, where they hovered spread out like a starry night before collapsing back into a nebulous cloud around his head.

Jackaroo always hiked fast. If I hadn’t been intent on being the first to arrive that morning he surely would have been. Jackaroo left Florida for the A.T. when he broke up with his girlfriend. He found out shortly after that she was pregnant. She knew him well enough to know he would be a wonderful father so long as he didn't have to think of his child and his aborted trip-of-a-lifetime in the same thought. She encouraged him to hike on, so he was hiking just as fast as he could; the sooner he finished, the sooner he could get back to Florida and his unborn child.

Pathfinder showed up next. He was a big guy, wide like a bear, with shaggy blond and black hair and a beard to match. He could have been a Viking in a different life. He got lost once in Maryland, which you wouldn’t know, but trust me, is an impossible state to get lost in. The A.T. just strolls along a paved path through a state park for a couple hours and then it’s over the railroad tracks to Pennsylvania. Ever since then he’s been hyper-active in identifying the Trail whenever it’s in doubt. He stepped up between Jackaroo and me and looked into the cracked Earth for a long, drawn-out minute measured only by the whine of mosquitoes and the soft but sharp stream of curses mumbled under his breath. His face looked like that of a kid from the short bus who interrupted a calculus class. Jackaroo and I glanced at each other, our raised eyebrows asking how long we should wait before laughing at the Pathfinder, when he suddenly found his line and snapped his fingers.

“See there’s our mark there. We’ll have to go over this first boulder—or can we get under it?—but then we need to make sure to go between those two. That’s all.”

Quiet Riot, who rarely opened his mouth except to tell a joke, and 10 O’clock, who was always the last one on Trail in the morning, were never far behind Pathfinder. The trio was friends from Ohio, and they had hiked together all the way from Georgia. 10 O’clock was telling Quiet Riot about a hotel bed he slept in once, how it was so comfortable he couldn’t bring himself to get out of it.

"So eventually the front desk stopped calling and just charged me for another night," he said.

They hadn’t been paying attention to where they were going, so Pathfinder had to give them the soccer-mom-reach-over to keep them from stepping on thin air.

"Figures," said Quiet Riot, "we give Schmeagle one day off on the whole Trail..."

Bewildered, 10 O’clock said, “There’s not an inch of flat ground down there. I’m putting my hiking poles in my pack, there’s no way we’ll be able to use them.”

As you might expect from three friends who hadn’t been apart more than half a day in five months, they had their thoughts and habits lined up like a sweet, old married couple. Pathfinder and Quiet Riot immediately agreed that that was a great idea, and set about doing the same thing.

Last to arrive were Mary Poppins and Professor Grayhairs. Mary Poppins was the only female in the group. Unfortunately for all the men but the Professor, she wore the shortest Hawaiian-print hiking skirt her college athlete legs had ever found. I tell ya, nice a sight as those legs were in the middle of the woods, better still was to be about a hundred feet behind her when some Dayhikers passed going the other way. Once they passed her, they'd put their dandy hands to their faces aghast and say things like:

"Like, omg, did you see her legs? She's got so many cuts she's going to get a microbial infection."

"Ugh, like, I know. She'll never get a razor over them smoothly again. Hey how much farther does the GPS say?"

Then they'd notice me about to trample them. I'd smooch at one, wink at the other, and press right down the center of the Trail without messin’ up my stride. They'd be forced to step aside or risk contamination at my touch. If I could manage one, I'd fart. Either way, I didn't yield to Dayhikers.

No, the veneer of dirt and blood didn't matter one bit to a thru-hiker—those were sexy legs. I have no idea how she got her name, though. She was just as sweet and cheerful-minded as you could be, and I always thought the real Mary Poppins was kind of a hard ass. But her cheerfulness was never tempered by any other state of mind, so she seemed kind of flat and child-like. It took a man like Professor Grayhairs to be her companion.

We called him Professor because he had spent most of his forty years traveling to far-flung corners of the globe, doing anything and everything you could think of. He knew a lot, about a lot. I imagine he spent a lot of that time without the company of women, so he was just as happy as could be: a forty-year old intellectual loner, walking through the woods with a sweet, twenty-something girl with wild legs and a Hawaiian-print skirt.

He had to rest pretty often on account of his bad knees, but even that made him suited to hike with Mary Poppins. She had a tendency to get distracted by any little thing she saw along the way. So if she wandered off around the shore of a lake to take pictures of the bull frogs, the Professor'd just sit against his pack there on the shoreline and smoke a pipe.

They sauntered up to the group and looked down the Notch. Mary Poppins said, her eyes wide, “Whoa! With all that climbing around down there, I need to change out of my skirt and into some shorts.” Against the silent protests of the rest of us, she turned and walked behind a tree. Professor Grayhairs said, “You guys go ahead. I’ll wait for her, I need to rest my knees anyway.”

Like paratroopers approaching their jump zone, we checked and rechecked each other's gear. Packs were zipped; shoes tied tightly, poles stowed securely. There was only one thing left to do.

Jackaroo picked up a handful of dirt and rubbed it between his hands, then said, "Let's do this thang."

That night the group reached the town of Andover and all checked into the Andover Guest House, a green and white old farmhouse as old as the Notch itself.

Professor Grayhairs was laid out on a lumpy gray couch with his legs on Mary Poppins’s lap. With her right hand she held bags of ice on the Professor’s knees, while with the other she flicked a spinner that was lying on his chest.

“Left foot yellow,” she said.

“I need to get under your leg, Quiet Riot,” Pathfinder said. “No, your other leg.”

“That’s not my leg.”

“That’s my leg,” Jackaroo said. “If I lower it, you can go over the top. But you have to keep your other leg in place cuz’ I’m sorta leanin’ on it.”

“Hey that’s cheating,” Mary Poppins said, with a smile.

“I prefer to think of it as team work.”

I was in a football lineman’s stance, trying to find a home for my foot by looking down through my shirt which hung loosely from my chest. A soft snapping of the Professor’s fingers drew my attention, and I saw that he was pointing me to a circle I hadn’t noticed.

“Thanks.”

The Professor held the board in place while his nurse gave it another spin.

“Right hand green.”

“No way I can make it,” I said. “I’m not tall enough.”

“Here, I can lean forward a little,” offered 10 O’clock.

I stretched forward, with three points of contact anchored to the mat, and tried to connect the fourth to its goal. I simply couldn’t reach. I couldn’t see in my mind’s eye a path from A to B. I was about to lunge for it, which would likely have ended with me flat on my face, when I felt a shoulder dock into my hips.

“Go ahead, man, I gotcha.” Pathfinder would have been in my way anyway if he didn’t move, so he leaned a little to help guide me in. I gripped a green circle, and was once again stable.  From my new vantage point, I was able to see that Jackaroo wasn’t going to make it unless he reached his arm under his leg, not over, so I let him know.

From my new vantage point, I was able to see that Jackaroo wasn’t going to make it unless he reached his arm under his leg, not over, so I let him know.

This time the professor gave a spin.

“Right foot blue.” This was met with groans and exasperations.

“Are you kidding me? I barely got to where I am now.”

“There’s no turning back, man. We gotta' go for it.”

There were many more calculated, gravity-checked movements of limbs to come. Like the herky-jerky walk of a chameleon, advances were made with trepidation.

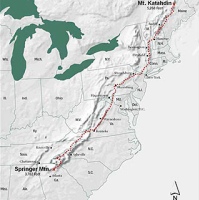

With a bit of teamwork in a traditionally solitary pursuit, we pushed further into the thicket as a group. We were masters of proprioception. With bonds of trust forged in the creation of an insular community, we moved under one mind. Like members of a herd, we looked out for each other. But we were no bewildered pack animals of the southern Appalachian Mountains. We were close enough to Mt. Katahdin to smell it. And anyone or anything else in the area could smell us, too.

We were a funk of thru-hikers.