- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

The Cud On History — Looking Back On The Great Depression In Australia |

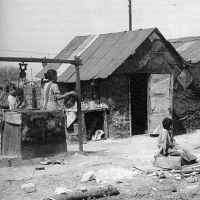

The impact of the Great Depression in Australia was considerable in the period from 1929 onwards. Whilst it is clear that the Depression was not a "sudden rupture" in events but rather part of a worsening economic trough that had its origins  in the early 1890's, the Depression certainly accentuated and intensified several problems.1 Unemployment statistics for Australia in the Depression years underestimated the extent of the severity of the problem: from mid-1930 until the last months of 1934, approximately one-fifth of all wage and salary earners were out of work, and in 1932-33 almost two-thirds of all breadwinners were receiving an income of less than the basic wage.2 Under such conditions we might assume that a large majority of Australians experienced suffering and deprivation in this period; unable to make ends meet, and unable to find any job security for the preservation of families and individuals alike. What becomes clear from an analysis of the Great Depression in Australia, however, is that the Depression certainly did not impact upon the lives of people equally (nor did it impact on some people's lives at all); and for those who were affected by the Depression, there is strong (though not indisputable) evidence that many of these people were still able to find happiness and stay resilient within what several historians and commentators have assumed must have been experiences marked only by degradation and crisis.3 Although in certain communities there was marked co-operation and a narrowing of class divisions as people shared in the fictional concept of an "equality of sacrifice" — that the Depression had affected all people, no matter what class, colour or gender they were, and that they must all therefore be prepared to bear some loss before a recovery was to take place.4 "Equality of sacrifice" was not completely realised, however, since one person's perceived 'sufferings' could be far removed from another persons understanding and experiences of suffering. Rather, the experience of the Great Depression was one of shared suffering within certain segments of society (most particularly in the working class), but with sharp contrasts between the hardships of one group or class within Australia and another.5

in the early 1890's, the Depression certainly accentuated and intensified several problems.1 Unemployment statistics for Australia in the Depression years underestimated the extent of the severity of the problem: from mid-1930 until the last months of 1934, approximately one-fifth of all wage and salary earners were out of work, and in 1932-33 almost two-thirds of all breadwinners were receiving an income of less than the basic wage.2 Under such conditions we might assume that a large majority of Australians experienced suffering and deprivation in this period; unable to make ends meet, and unable to find any job security for the preservation of families and individuals alike. What becomes clear from an analysis of the Great Depression in Australia, however, is that the Depression certainly did not impact upon the lives of people equally (nor did it impact on some people's lives at all); and for those who were affected by the Depression, there is strong (though not indisputable) evidence that many of these people were still able to find happiness and stay resilient within what several historians and commentators have assumed must have been experiences marked only by degradation and crisis.3 Although in certain communities there was marked co-operation and a narrowing of class divisions as people shared in the fictional concept of an "equality of sacrifice" — that the Depression had affected all people, no matter what class, colour or gender they were, and that they must all therefore be prepared to bear some loss before a recovery was to take place.4 "Equality of sacrifice" was not completely realised, however, since one person's perceived 'sufferings' could be far removed from another persons understanding and experiences of suffering. Rather, the experience of the Great Depression was one of shared suffering within certain segments of society (most particularly in the working class), but with sharp contrasts between the hardships of one group or class within Australia and another.5

The suffering of the Great Depression was not evenly spread. As official statistics indicated an average level of unemployment of 29% — typical for the period (and yet an underestimation)6 — it was the working classes and those who became unemployed who bore the greatest brunt of the Depression. As Stuart Macintyre discussed in his study of Australian responses to unemployment during the Depression:

The suffering of the Great Depression was not evenly spread. As official statistics indicated an average level of unemployment of 29% — typical for the period (and yet an underestimation)6 — it was the working classes and those who became unemployed who bore the greatest brunt of the Depression. As Stuart Macintyre discussed in his study of Australian responses to unemployment during the Depression:

"Treasury officials and spokesmen for the financial institutions were heard to insist that the only responsible policy was to reduce the public deficit, and warn that recovery had to come from the private sector.... national conferences produced plans for restraint, fiscal responsibility, and the sharing of sacrifice across the community- but leaving the unemployed to shoulder the burden." 7

That is, the inability of the State and Federal governments of the Depression era to satisfactorily pursue successful policies for recovery meant that the suffering would continue to suffer. Where work could be found, it was often only for the short term, and because of the economic climate and rarity of such work on offer, low wage rates and poor working conditions had to be tolerated — there was always another hungry person in the employment queue who would be willing to do such work.8 The situation was further worsened when, in 1931, the Arbitration Court imposed a 20% cut in the wages of all workers.9 Forms of government aid such as employment on public works were few and far between, and for the majority of the unemployed they were forced to fall back on sustenance payments or rations to survive.10

the economic climate and rarity of such work on offer, low wage rates and poor working conditions had to be tolerated — there was always another hungry person in the employment queue who would be willing to do such work.8 The situation was further worsened when, in 1931, the Arbitration Court imposed a 20% cut in the wages of all workers.9 Forms of government aid such as employment on public works were few and far between, and for the majority of the unemployed they were forced to fall back on sustenance payments or rations to survive.10

The impact of unemployment in the Depression went beyond such basic hardships as hunger and financial loss, however. Losing a job broke the work and leisure routines of an individual's life, and the victim further lost the company of workmates. There was also an obvious loss in self-esteem for thousands of people, and migrants, small business owners and the self-employed were particularly susceptible.11 Above all, the Depression had a significant >impact upon the Australian family unit and upon gender relations. Many men who lost the ability to support their

Women suffered in the Depression as well; they had the added stress of having to seek out work themselves when their husbands could find none, as well as employing traditional women's skills to try and hold together and manage their households as effectively as possible under the circumstances.12 Where some women were fortunate enough to find employment, some criticised them for stealing 'men's jobs'.13 The employability of children as cheap labour during the Depression and the added costs of schooling meant that many children lost opportunities for education and were pressured to leave school and earn money. As one lady recalled, in 1929 and aged only thirteen, her stepfather took her up to the local mill to work: "... you didn't have to show papers or anything."14 Upon reaching adulthood many child workers were subsequently laid off and left without any substantial job skills so that their employers could avoid paying the higher wages.15

Public charities helped to an extent to alleviate the problems of the Depression, but resources were obviously scant, and the negative stigma attached to receiving from charities limited many people's access and willingness to accept these forms of support. Whilst historians such as David Potts have discovered a strong drive of generosity and community spirit during the Depression,16 there were also limits to people's charity, and the unemployed were more likely to receive aid from others in the form of individual generosity and  'gift-relationships' rather than as help to the out-of-work as a group.17 Government welfare in the period was clearly regarded as a charity and not a right, and the emphasis was upon maintaining the social order and stability, and encouraging a stronger work ethic.18 As Ray Broomhill identified, "The ordering of priorities during the crisis made it clear that the welfare of the unemployed was generally subordinate to the overriding concern for political stability, economic orthodoxy, and the protection of established financial interests."19 Regardless of the type of aid available for the unemployed working classes, all forms of relief were characterised by one element- uncertainty.20

'gift-relationships' rather than as help to the out-of-work as a group.17 Government welfare in the period was clearly regarded as a charity and not a right, and the emphasis was upon maintaining the social order and stability, and encouraging a stronger work ethic.18 As Ray Broomhill identified, "The ordering of priorities during the crisis made it clear that the welfare of the unemployed was generally subordinate to the overriding concern for political stability, economic orthodoxy, and the protection of established financial interests."19 Regardless of the type of aid available for the unemployed working classes, all forms of relief were characterised by one element- uncertainty.20

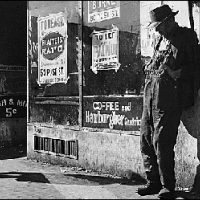

Whilst the unemployed and the working classes suffered the most during the Depression, this is not to say that other groups within society did not perceive themselves to have suffered — it is just that such suffering was not necessarily in proportion to the suffering of others. The Depression only impacted briefly upon the profits of several big businesses and companies such as Broken Hill Proprietary Ltd. and the Colonial Sugar Refinery; in fact few such companies experienced losses, and were able to continue issuing dividends to their shareholders during the Depression crisis.21 If anything, the Depression helped to strengthen such companies as they took advantage of weak competitors in the aftermath of the Depression via various mergers and takeovers.22 Certainly the more securely employed and more private middle-classes suffered more than the casual working classes during the Depression, the latter having been hardened by the insecurity of their lifestyles. Throughout the period, however, "... if some members of the dress-circle suburbs were forced to economise, others remained affluent."23 Indeed many wealthy families were able to survive the Depression without any disruption to their lives at all, save for their activities in charity-raising that was a part of many people's social calendar anyway.24 As John Shields commented, "Very few of Woollahra's leading citizens would have been reduced to eating Irish stew, bread and dripping or 'specked fruit'."25 When a middle class individual might have been  unable to buy the latest fashions during the Depression years, therefore, there was certainly no equality of sacrifice that could be compared to the unemployed man foraging a rubbish bin for his dinner, even if the middle class person had perceived his own sacrifice and suffering as significant in the context of his own class and experiences.

unable to buy the latest fashions during the Depression years, therefore, there was certainly no equality of sacrifice that could be compared to the unemployed man foraging a rubbish bin for his dinner, even if the middle class person had perceived his own sacrifice and suffering as significant in the context of his own class and experiences.

In a crisis that was on such a large scale as the Depression, many saw the events of the period as beyond the control of human agency, and it was difficult for many of the unemployed to find a focus for their discontent.26 Where the suffering was clearly uneven throughout society, the Depression contributed to increased class resentment and social division,27 and the working classes gradually employed tactics of resistance during the period (particularly against the authorities) to try and safeguard their rights and stay resilient. Such activities included deputations, protest marches, and oppositions to evictions, which at times resulted in violent clashes with police.28 Although many pursued strikes and radical political solutions as a means of relief, such activity was difficult in the face of fierce government repression, and because many were willing to work, as aforementioned, whether their rights were safeguarded or not, simply as a means of 'getting food on the table'.29 Furthermore, the tendency for many to turn towards focusing on self-preservation rather than group activity during the Depression meant that Marxist and other such organisations would find it difficult to attain a firm grip, even if they alarmed the governments in power.30

Within this Depression-era atmosphere of suffering and sacrifice, however, evidence drawn from oral histories  and other sources suggests that within this crisis many people were nonetheless able to find happiness and contentment, and remain strong amidst uncertainty. Individuals drew on heroes from the area of sport and elsewhere to draw inspiration, and communities and families showed a generosity towards each other that many believe has not been seen since. Whilst information from oral histories must be treated with the same care as all forms of historical evidence, oral accounts by people from the Depression era (as collected by David Potts) can prove invaluable in providing information and viewpoints (though obviously subjective) which can add another dimension or even dispel myths which have been associated with the period.

and other sources suggests that within this crisis many people were nonetheless able to find happiness and contentment, and remain strong amidst uncertainty. Individuals drew on heroes from the area of sport and elsewhere to draw inspiration, and communities and families showed a generosity towards each other that many believe has not been seen since. Whilst information from oral histories must be treated with the same care as all forms of historical evidence, oral accounts by people from the Depression era (as collected by David Potts) can prove invaluable in providing information and viewpoints (though obviously subjective) which can add another dimension or even dispel myths which have been associated with the period.

Endnotes

- Ray Broomhill, Unemployed Workers- A Social History of the Great Depression in Adelaide, University of Queensland Press, 1978, p.1.

- Macintyre, Stuart. The Succeeding Age, Oxford University Press, 1993, p.275.

- Note the findings discussed in David Potts, "A Positive Culture of Poverty Represented in Memories of the 1930's Depression", JAS, 26, May 1990, pp.3-14, and David Potts, "Tales of Suffering in the 1930's Depression", JAS, 41, June 1994, pp.56-66.

- See Macintyre, op.cit., p.285.

- Broomhill, op.cit., p.10.

- Ibid., p.2.

- Stuart Macintyre, in Jill Roe (ed.), Unemployment- Are There Lessons from History?, Hale and Ironmonger, 1985, p.22.

- Wendy Lowenstein, Weevils in the Flour- An Oral Record of the 1930's Depression in Australia, Scribe Publications, 1978, p.4. "At best the unemployed lived a hand-to-mouth existence with spells of relief work or sustenance payment supplemented by food bundles and queuing at soup kitchens. At worst they lost everything, including the roof over their heads." Macintyre in Roe, op.cit., p.25.

- See Broomhill, op.cit., p.7.

- Macintyre, op.cit., p.277.

- Ibid., p.278.

- Note Diane Bell's discussion of Depression era women creating "luxuries with leftovers", and adhering to the dicta "waste not want not". Diane Bell, Generations: Grandmothers, Mothers and Daughters, McPhee Gribble/Penguin Books, 1988, p.33.

- Lowenstein, op.cit., p.2.

- John Shields (ed.), All Our Labours — Oral Histories of Working Life in Twentieth Century Sydney, N.S.W University Press, 1992, p.27.

- Ibid., p.27.

- David Potts, "A positive culture of poverty represented in memories of the 1930's Depression, op.cit., pp. 3-14.

- "As individual supplicants, the unemployed were tolerated and offered whatever charity was available; collectively, or when they asserted rights, they were denied recognition." Macintyre, op.cit., p.281. Also note p.279.

- Ibid., p.284.

- Broomhill, op.cit., p.7. See also Peter Cochrane, Industrialisation and Independence — Australia's Road to Economic Development, 1870-1939, University of Queensland Press, 1980, pp.124-135.

- Macintyre, op.cit., p.285.

- "The profit of B.H.P itself dropped from £291,577 in 1927 to £83,257 in 1931 but quickly recovered and by 1935 had soared to £670,442. Broomhill, op.cit., pp.8-9.

- As occurred with General Motors and Holden in South Australia. Ibid., p.9.

- Macintyre, op.cit., p.287.

- Shields, op.cit., p.139.

- Ibid., p.135.

- Macintyre, op.cit., p.280.

- Lowenstein, op.cit., pp.6-7.

- Such as occurred during the nation-wide day of protest on March 6, 1931. Macintyre, op.cit., p.281.

- See Macintyre, in Roe, op.cit., p.26.

- Note the discussion of the New Guard, formed to oppose disorder and especially Jack Lang, in Lowenstein, op.cit., pp.5-7.

References:

Bolton, G.C., A Fine Country to Starve In, University of Western Australia, 1972.

Cashman, Richard., and McKernan, Michael (eds.), Sport in History — The Making of Modern Sporting History, University of Queensland Press, 1979.

Cooksey, Robert (ed.)., The Great Depression in Australia, Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 1970.

Louis, L.J and Turner, Ian (eds.), The Depression of the 1930's, Cassell Australia, 1968.

Potts, David. " 'There's nothing squashed about me': A Reply to Scott and Saunderson Poverty in the 1930's Depression", pp.50-55.

Scott, Joanne., and Saunders, Kay. "Happy Days are Here Again? A Reply to David Potts", JAS, 36, March 1993.

Spenceley, Geoff. "The Social History of the Depression of the 1930's on the Basis of Oral Accounts: People's History or Bourgeois Construction?", JAS, 41, June 1994, pp.35-49.