- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

The Complexity of Indigenous Language: |

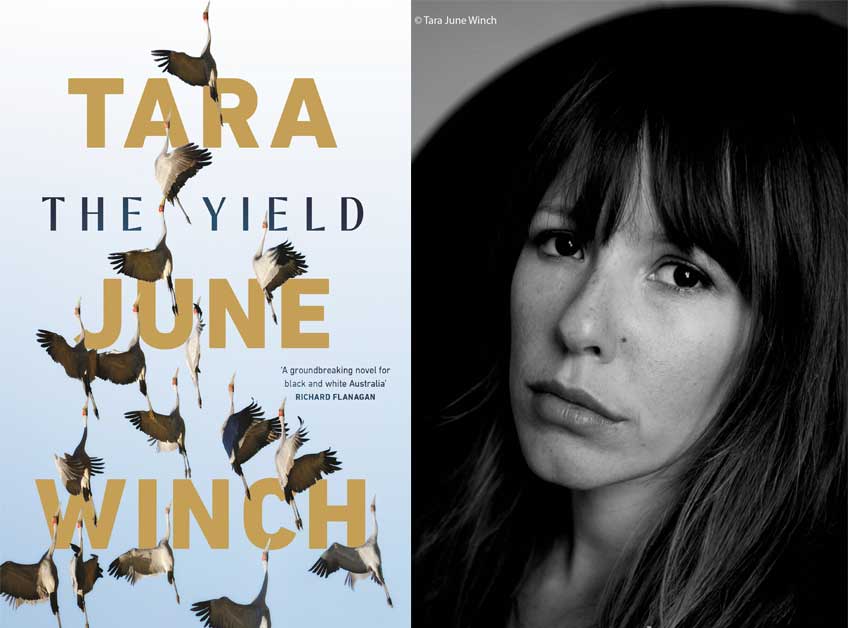

Tara June Winch’s Swallow the Air was a stunning first book of short stories for such a young writer. Now her novel The Yield maintains that high quality. While Tara June acknowledges some other Indigenous Australian writers of fiction and history including Behrendt, Lukashenko, Pascoe and Reynolds, this ambitious book has a unique format and style. As well as being a very readable novel, The Yield makes an important contribution to the United Nations International Year of Indigenous Languages.

The novel has three components running parallel. The main story which drives the narrative concerns August who has returned from England for the funeral of her grandfather known as Poppy. Her ancestral Gondawindi land has parallel identities as Massacre and as Prosperous. But her grandfather was working on a dictionary of Wiradjuri or Murrumby words and when August learns about this, her search for Poppy’s book and investigation of the language provide her with the possibility of saving their traditional lands from a mining company.

Interspersed with the story of August’s reunion with family and a selection of terms and their special and relevant meanings is the third strand in the form of correspondence between a Lutheran missionary and the authorities. Reverend Greenleaf’s name was Anglicised partly to avoid the persecution which affected so many immigrants from German provinces during the first world war. He feared that internment would sap the life from him but was prepared to speak out in defence of the Aboriginal people in his care. Whether because of his Christianity or because he also suffered persecution he refused to co-operate in the cruelty settlers inflicted on the people at his mission. August’s discovery of his correspondence adds a further element to her quest for evidence that her family’s land is sacred. The yields are multi-layered and powerful both for August’s outcome and for the literary quality of Tara June’s writing.

August’s sister Jedda disappeared when they were teenagers and the missing sibling haunts August who feels guilty. Winch uses a brolga’s dance to explore the idea of a spirit freed. The yield also has several meanings literal and allegorical. The story’s conclusion turns on one of those meanings.

I was obviously too engrossed in the stories to be flicking ahead because it was a great surprise to discover the Wiradjuri dictionary almost as an appendix. Tara June presents the words in reverse alphabetical order. She also mentions the work of Stan Grant senior and John Rudder in compiling the Wiradjuri dictionary. Indigenous languages are being revived and valued.

Tara June points out too that language is vital to the maintenance of culture. Some cultural practices can be referred to only in language. Many of the words she has chosen to highlight have no direct parallel or translation in English. The experiences from which they arise are unique. For example dhaganhu ngurambang or ‘where is your country?’ is not about geographical location specifically but about origins and kinship: ‘Who is your family?’ and ‘Are we related?’

Destruction of languages therefore becomes a form of genocide. Before ‘colonisation’ or invasion in 1788 there were some 250 Indigenous languages in Australia subdivided into 600 dialects. It is estimated that about 30 survive. The Yield is an appropriate book to appear during the UN International Year of Indigenous languages. It shows that the promise of the early writings by Tara June Winch have been fully realised in this mature historical novel of the survival of the Australian spirit.

2019 © Tony Smith

A former academic, Tony Smith has written extensively on a wide range of subjects as diverse as folk music and foreign policy issues in the Australian Review of Public Affairs, the Journal of Australian Studies Review of Books, Overland, the Australian Quarterly, Eureka Street, Online Opinion and Unleashed.