- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

An American In Cornwall |

Maybe it was the ten years in Los Angeles, perhaps it was the divorce or even the moon-faced cretin that we had to refer to as “The President”, but regardless, in 2001 I hit critical mass and fled the United States. I had a few thousand dollars and an acceptance letter into Cambridge University’s CELTA program. CELTA (Certified English Language Teacher to Adults) was a way for me to earn money and stay in Italy, I thought indefinitely. Seven days later thirteen Saudi Arabians flew four planes into various targets in the United States and a fuse was lit.

I remained out of the country for the remainder of 2001, and most of 2002. I taught English, drank copious amounts of wine, and enjoyed long delicious mornings in bed with my Austrian girlfriend. Ultimately, looking back, I was just another ugly American on extended shore leave, leaving a wide swath of destruction and a jagged emotional wake. The political atmosphere of the world had changed forever, Italy no longer had permissive attitudes toward American or British visitors and after dodging the Carbanari police for a year I fled Verona over the Alpi to Innsbruck and ultimately “home” to America.

I stepped off the plane into a changed country, one with a suspended Bill of Rights, the only “real” distinguishing piece of paper between us and the rest of the world. Everybody has constitutions, but nobody had such a wonderful concept of citizenry with “inalienable” rights that protect the many from the few. A year earlier, Peter Levy, a crazed Australian cinematographer said as an American, “I’d never know how wonderful it was to have a Bill of Rights.” To be born with rights was an alien concept, even to an Aussie, with whom we as Americans find similar cultural morays. We were standing in the parking lot at Warner Brother studios, and he was holding his citizenship paperwork in his hands. The words meant nothing to me- another crazy Australian. Los Angeles is full of them. Later I would see a tiny man standing on the deck of an aircraft carrier declaring “victory”. Victory, yet thousands of Americans, and hundreds of thousands Iraqi noncombatants were about to die. As I stared blankly at the screen, the spittle running over my lips and down my chin, I imagined the front door of my house caving in under the pressure of a federal battering ram, federal agents armed with everything except the warrant for search and seizure. Of course I had nothing to hide, but these events and the mere possibility of them happening started to weigh on my perceptions of America.

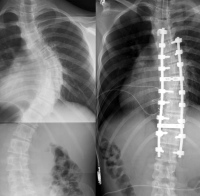

Flash-forward a few years and I’m living in Reading, Pennsylvania and selling pedicle screws for Globus medical, a spinal device company. I’ve joined the rat race and work for a start up company who posses the growth potential of Microsoft in the 1990’s. Globus’ chief engineer and owner developed a flexible metal rod, an element that allows some limited motion within the construct. Up until this point spinal fusions have been guided by the principle that the vertebrae must be fixed (fused) in an absolute rigid construct, metal supporting bone as scaffolding supports a wall. It has been known for some time that slight agitation of fusing bone creates stronger bone, and a faster healing process (Wolfe’s Law). Globus has developed the technology that cuts tiny spirals in the titanium rods that facilitate this process.

The spinal device racket is the fast track to becoming a multi-millionaire, without having to be creatively talented, intelligent, or even lucky. It helps to be good looking, well groomed and have an almost sociopathic ability to manipulate people. One must also have an unquenchable desire for material possessions, and the competitive nature of an athlete. I won’t go so far as to say I’m creatively talented, or even intelligent, but I’m certainly not cut out for sales. My primary handlers, who run the company, are intelligent, but my comrades, my buddies, the guys you work with every day, are vacuous overachievers who support the “War on Terror” and break eye-contact during conversation when the new 500 series Mercedes passes us by exclaiming, “If I hit my numbers this year that could be me”

I drive a Nissan Sentra, which gets thirty-six miles to the gallon, but leaves me with the dregs of the society and certainly the sales force. I try desperately to convince my comrades and handlers that we need a national health care system, and that all insurance companies are evil. My comrades and handlers explain to me that social reform would make our entire business extinct and that I’m communist swine. I’m miserable. I drive from hospital to hospital, from surgery to surgery, listening to doctors and sales reps and nurses and everybody discussing money, vacations and second homes. I spend hours on the roads squeezed in between SUV’s, pick-ups and land arks. The landscape of southern New Jersey is one continuous strip mall, broken up with car dealers, and peppered with fast food joints. The scenery doesn’t change when I cross into Pennsylvania, and even when I drive through that which appears to be rural areas, I see the malls peeking between the trees, the billboards advertising the virtues of my next triple by-pass wedged between two pieces of wonder bread. We’ve declared a war on drugs, but we’re all stoned on McShit, Wall Mart, and trans fats. The Enron oligarchs get sentenced, but no-body asks about Dick Cheney’s energy commission; nobody can, the records are sealed. National Security. Despite the fact that oil is a finite source of energy, American cars are getting the same gas mileage they did in the sixties. Israel bombs Lebanon, wages war on playgrounds and apartment complexes while America sits silently- “no cease-fire until we achieve a lasting peace.” The list goes on an on, and the fuse that was lit in my opening paragraph reaches its end, yet the explosion is without noise. It happens in the vacuum of my scream of outrage, which has sucked all the air out of the room.

I quit my job, and move out of my apartment into my mother’s house. I don’t even know what tactical alert means, but I know I’m on it. I let Nissan repossess my Sentra, which is more like a disposable lighter than a car. My money is withdrawn from my account, and put in my mother’s name. I go to the mall and buy socks and good hiking boots. I’m leaving and I know wherever it is I’m going I’ll be doing a lot of walking. My mother is Swedish and because we have immediate family there, it might possibly be a place I could live. I’ve been to Sweden, and I love it, but for a variety of reasons, I know it would be a difficult place to immigrate to. Swedish is a difficult language to learn, and on the practical side of things the Swedish Kroner mops up the British pound and the pound cleans counter tops with the dollar. My mother suggests England, a country I haven’t been to since the early eighties.

My mother has an old friend named Jane, formerly Jane Mills, but divorced and re-married as Jane Rogers. Jane is now living in Cornwall, in southern England and running a garden and bed and breakfast. Jane probably remembers me as the thirteen-year-old American who terrorized her very existence for a summer in the Cotswold’s. I had a lot of firsts in England, first cigarette, first hard cider, first beer, first hangover, and all at Jane’s expense. If she does remember me, there’s a good chance that she prefers to keep me as a memory. My mother convinces me to send her an email, and I do, crossing my fingers hoping for a chance at freedom.

Let me back up a bit here... I graduated from film school in 1990, and trucked on out to Los Angeles where I lived and worked my way up through the film business primarily as a grip, but with hopeful aspirations of writing, directing, and producing films. Basically I wanted to be the next Francis Ford Coppola, but it turns out that job was already taken. I do not come from a wealthy background, and I am the consummate under achiever. Talent and wealth are not mutually exclusive, but it helps to have both so you can hang on by your fingernails in Los Angeles. Once you’re in that game, opportunities will present themselves, the credo being: luck is simply the event that happens when opportunity meets preparedness.

I had to work to support myself, and to work as a film technician you have to be good. To be good you had to be skilled. To be skilled you had to stay on the learning curve. To stay on the learning curve you had to put yourself in as many situations as possible. That means never saying no. Every time that phone rings you pick it up and regardless of the pay, the budget, or the impossibility of realizing someone’s creative wishes, whilst running the risk of being crushed by iceberg sized egos, you say, “yes”. Living on that treadmill leaves no time for writing the next Lawrence of Arabia, or Godfather. I worked constantly, and eventually became a highly regarded grip, but the vessel remained empty. I attempted to write scripts, even had representation through an old college friend who was making millions as a literary agent. But it was to no avail, the only split focus in this story was in the Zeiss lens attached to the body of the Panavision camera. I guess the “short” of this incredible “long” is that somewhere in me was a novel, or at least a chance of cobbling some words together, and what I needed to do was create an opportunity for myself, a situation, that would allow me to live, yet provide an environment to shed a couple words on paper.

To be good you had to be skilled. To be skilled you had to stay on the learning curve. To stay on the learning curve you had to put yourself in as many situations as possible. That means never saying no. Every time that phone rings you pick it up and regardless of the pay, the budget, or the impossibility of realizing someone’s creative wishes, whilst running the risk of being crushed by iceberg sized egos, you say, “yes”. Living on that treadmill leaves no time for writing the next Lawrence of Arabia, or Godfather. I worked constantly, and eventually became a highly regarded grip, but the vessel remained empty. I attempted to write scripts, even had representation through an old college friend who was making millions as a literary agent. But it was to no avail, the only split focus in this story was in the Zeiss lens attached to the body of the Panavision camera. I guess the “short” of this incredible “long” is that somewhere in me was a novel, or at least a chance of cobbling some words together, and what I needed to do was create an opportunity for myself, a situation, that would allow me to live, yet provide an environment to shed a couple words on paper.

But on to Cornwall…

Part II of An American In Cornwall will appear in our June issue.